|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Jul 17, 2014 13:55:15 GMT -5

Step 43 – Filing the Bolt Welds __________________________________________ Some things are better done by hand, and this is one of them. Trying to square edges close to a cylindrical mating point is tough. We used flat files to do this, starting with an aggressive profile and then progressing to a fine tooth. Emery cloth removed the file marks completely:    All that remains is to polish the handle, but we’ll do this after welding it to the shaft. Bolt timing – how the handle engages the receiver cam is big. If it cams in before the lugs meet the raceway, it binds. We mocked it up and believe we’ll need to grind some relief into the upper front edge. We’re going to hold off on doing so until it’s welded though.   -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

cmillard

.375 Atomic

MOLON LABE

MOLON LABE

Posts: 1,996

|

Post by cmillard on Jul 18, 2014 6:48:40 GMT -5

keep up the great work!

|

|

|

|

Post by vashooter on Jul 21, 2014 6:36:43 GMT -5

Im totally amazed at this project my head is spinning

|

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Aug 26, 2014 15:09:40 GMT -5

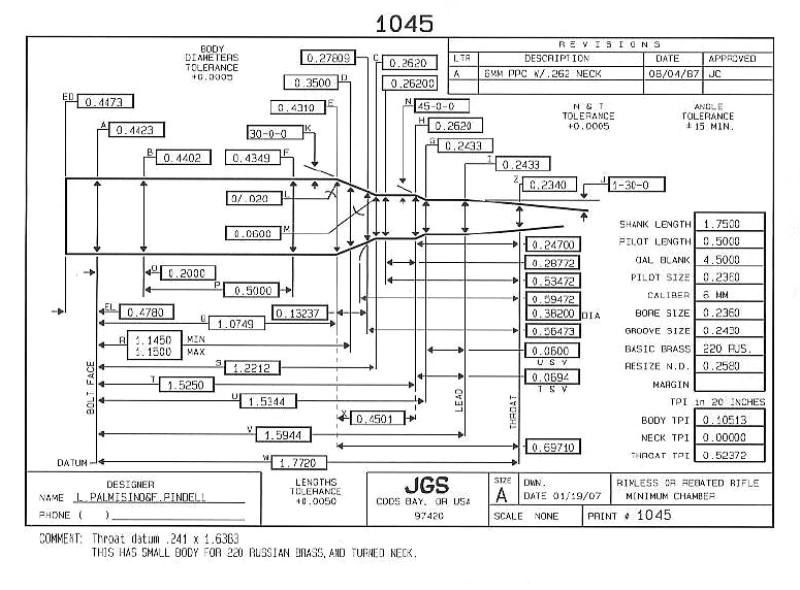

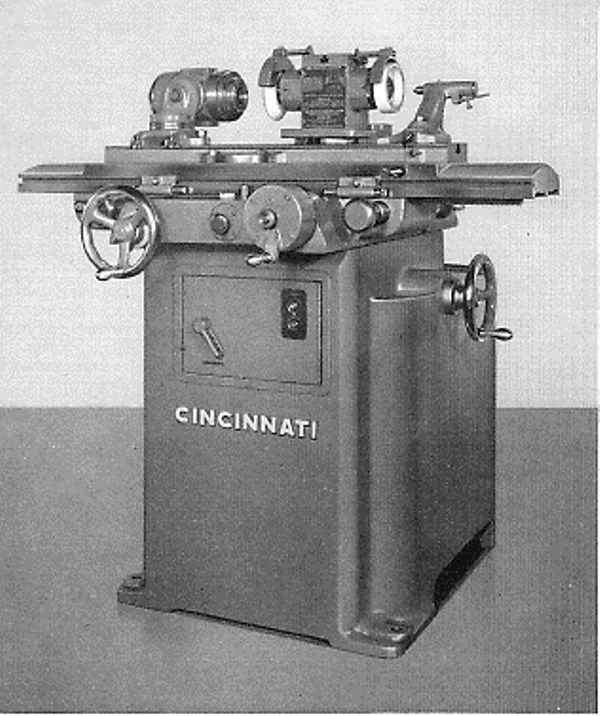

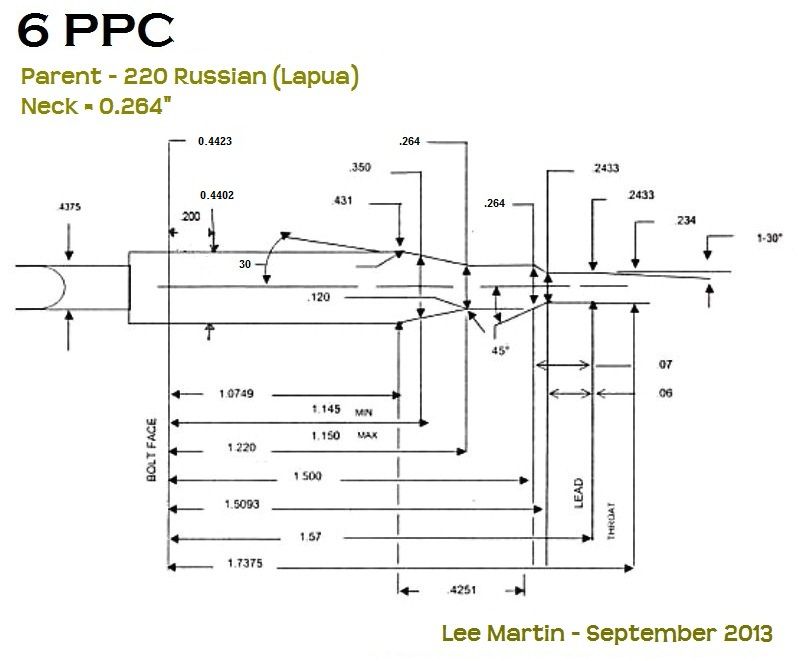

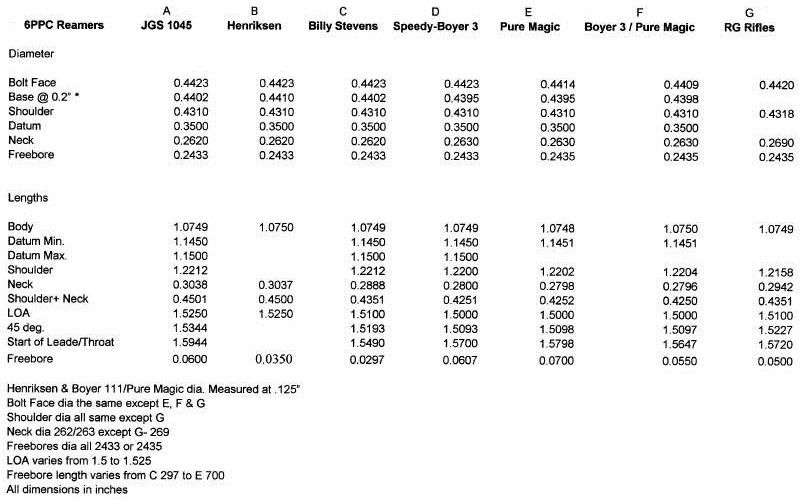

Decision Time on the Reamer _______________________________ If you recall, we adjusted our reamer dimensions last fall. What we landed on is essentially JGS’ 1045 6 PPC grind. This one has some good history. Back in the 1980’s, Keith Francis (JGS Tools) worked with Ferris Pindell and optimized the PPC. Their goal was to create a minimal spec chamber for cases formed from .220 Russian. The year was 1987 and that print mates extremely well with Norma and Lapua brass. Indeed, probably 80% of the reamers used in competition are exact or very close derivatives of the 1045. Here’s the schematic:  Pindell covered the 1045 in a Precision Shooting interview from the 1990’s. He felt 0.4402” at the 0.200” mark was ideal for close management of the base, but wide enough to eliminate bolt click and hard extraction. Interestingly, he said he’d go a little thicker on the neck if he were to start over. Sako brass from the 70’s and 80’s sometimes took turning to 0.262” for complete clean-up. Lathing the wall 0.0085” and seating 0.2435 bullets nets 0.2605”. That’s leaves 0.0015” total clearance or 0.0075” per side. Nowadays, everyone uses Lapua or Norma and they true between 0.266” and 0.269”. Out of the box quality has also improved, enough that a small, but growing group compete “no-turn”. Anyways, Pindell said he’d up the neck to 0.264” for a hair more longevity and tension. The late H.L. Culver, who sucked us into benchrest, shot 0.264” on his PPCs too. For those reasons, I chose the same for my 6. Build or buy... My dad started making his own roughing and finishing reamers around 1981. Our shop is pretty old school. There’s no CNC and we’ve only been digital readout since 1994. Reamers are ground on a 70’s vintage Cincinnati #2 Tool & Cutter grinder. These were top of the line in their day and still hold to a ten-thousandth. The downside is they have long set-up times and their repeatability can’t touch modern computers. Dad’s concern was being able to duplicate our reamer once wear takes out the original. And in benchrest, you’ll go through a few. A strong shooting season means 4 to 5 barrels. Or in six years of competition that reamer sees 25 to 30 blanks. The other fly in the ointment is the throat. Dad doesn’t grind it into his finishers, he throats separately. The practice is equally accurate to an all-in, but repeatability barrel to barrel is a risk. You see, in tuning these rifles free-bore becomes essential. Not only is it designed for a specific ogive, changing the depth a few thousandths in or out can show-up on paper. At his urging, I decided to have the throat and lead integral to the reamer. Enter the commercial grind experts like Dave Kiff, Keith Francis, and Hugh Henriksen. With computer controlled output, they’ll cut reamers exactly to print every time (ie, precision to the ten-thousandth). A stock photo of a Cincinnati #2 Tool & Cutter Grinder:  I compared my final drawing (shown below) to JGS’ 1045 spec sheet. The only difference was a 0.264” neck instead of the longstanding 0.262”. That shouldn’t be a problem I thought, so I called JGS. I figured it would be custom on the 1045 until their rep schooled me. “Oh, so what you’re really after is our 1046”, she replied. Apparently they’ve been making a 0.264” on 1045s for a while now. Listed at $160, the quoted turnaround was only 4 weeks. For that price and interval, it doesn’t pay to make our own. I ordered one last Friday and should have it by the end of September. My goal is to have the action wrapped by the time it arrives. Desired chamber as drawn by me last September:  Since I plan on shooting 9-ogive Bart Sauter Ultras, the 0.060” throat will work perfectly. I should call out other reamers used throughout the sport. The second most common are the tight base PPCs made famous by Tony Boyer and Speedy Gonzales. These have the same shoulder as the 1045, but reduce the 0.200” mark to 0.4395”. Many believe this puts less strain on the head and preserves primer pockets. It may, but after talking to a handful of 1045 shooters, they’re getting 30 – 50 reloads on their Lapua hulls. More importantly, bolt click isn’t as prevalent with 0.4402”. It seems inconceivable that 0.0007” makes a difference, but at 70,000 PSI it can. Here’s a chart showing other reputable grinds:  This change of plan alters my FL sizer strategy, but in a good way. More on that later, because how these guys size the PPC is involved. -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Aug 26, 2014 16:09:26 GMT -5

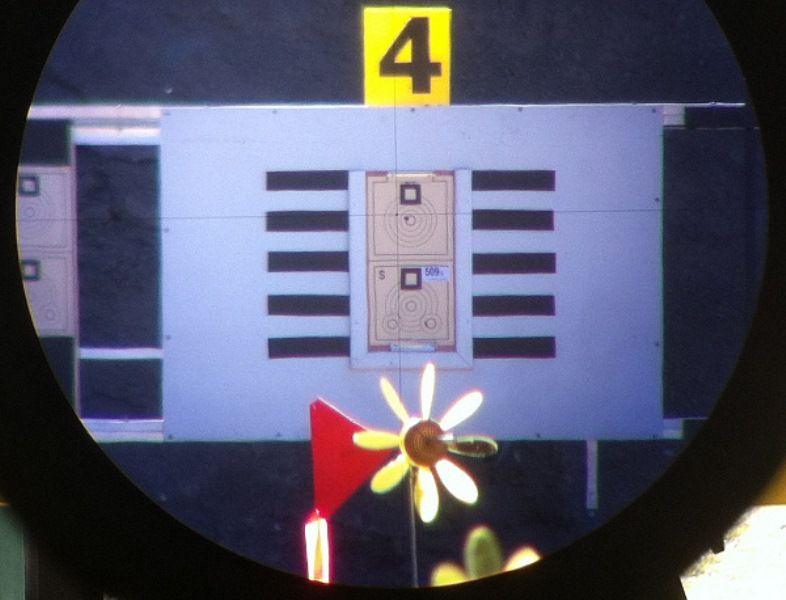

A neat video of Charles Huckeba putting five-shots into just under 1/4" at 200 yards (1/8 MOA). You'll see he found his conditions and sent all five downrange in 30 seconds: Here's the view of the actual target at 200 yards. The scope is a 50X March, 1/16" dot reticle:  -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by maxim2841 on Sept 10, 2014 21:59:05 GMT -5

very great,excellent

|

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Sept 18, 2014 19:07:50 GMT -5

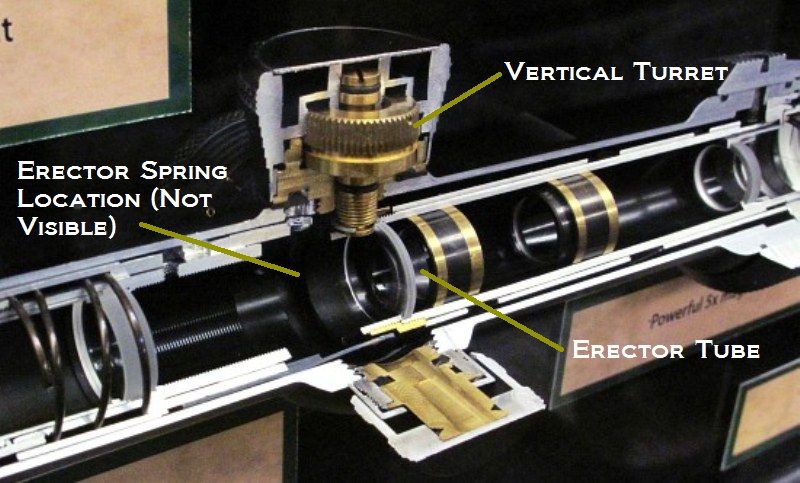

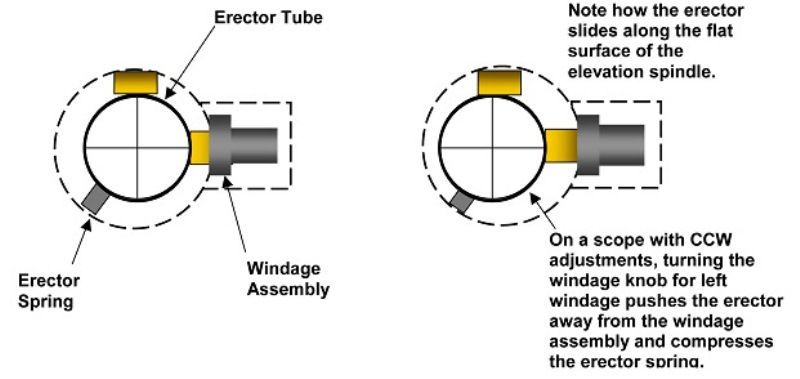

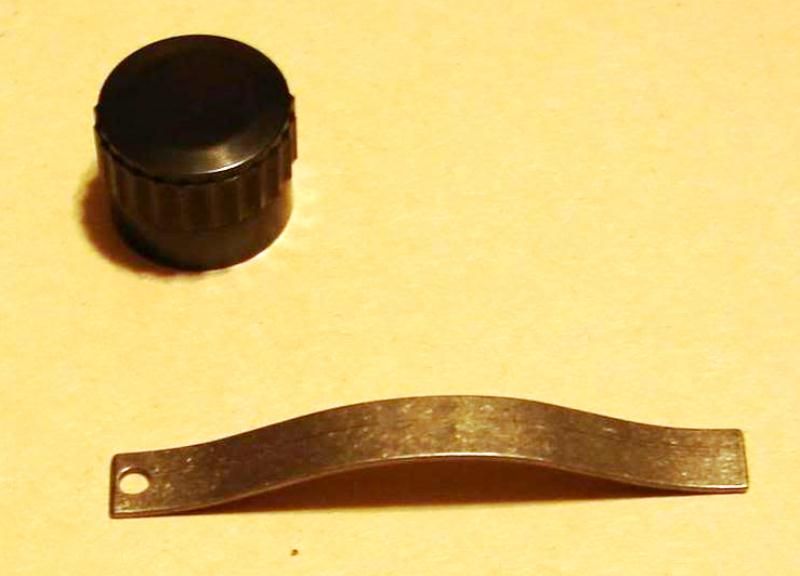

Scope Considerations – Part I _____________________________________ We’re a long way from needing a scope on this project. But it never hurts to think ahead and optics are a major part of BR. Glass features and quality have really advanced since the sport formed in the late 1940s. For the first 30 years, Unertls and Lyman Target Dots ruled the roost. By the 1980s, Leupolds claimed most of the market and held that position along with the Weaver T-Series. Nowadays we have a host of comp-worthy models to choose from. March, Leupold, the Weaver T and new XR series, Nightforce, Sightron, and Schmidt & Bender are the chief players. Leupold Competition 45X  Magnification and clarity are assumed prime traits in benchrest. While important, neither is as fundamental as repeatability and holding point-of-aim (POA). If the scope won’t do either, a 60X perfectly clear reticle won’t do you a damn bit of good. Here’s why. In short-range BR, you’re competing in 100 & 200 yard aggregates. Scope adjustment, at least for vertical, is a given. It’s also not uncommon to dial the turrets for changing conditions, or in other words, “holding off”. Repeatable tracking is a must have. A mere few thousandths of instability will kill aggs at 100 yards, and at 200, forget it. What governs rock solid tracking? To answer that question we need to get into the guts. The scope body houses the erector tube, which contains the reticle, or cross hairs. This butts against the turrets and moves when adjusted. Counter to each turret is a rebound system, usually comprised of flat springs. Here’s a cross-sectional view of a Weaver:  Over time, erector springs can weaken, stick and fail to rebound, or even shift slightly. To illustrate their importance, 0.001” in unsolicited movement equates to a 0.125” change in POI at 100 yards. Double that when you move to 200 paces. Clearly, that’s material when trying to stick five-shots in a 0.00 – 0.20” spread. In the golden era of benchrest, guys fought barrels, bedding, bullet concentricity, and triggers. Combined they far outweighed the risk of scope movement. And they still do, just less so. That’s because the quality of those components has improved tremendously in the past 30 years. Excluding barrels, the modern era fights optics more than any other input. But proving the existence of scope POA gremlins isn’t easy (more on that in the next segment)  No scope is immune to what I’ve just described, not even best in-class. Take Leupold 36, 40, and 45X Competitions for example. They’re clear, lightweight, are easily dialed, and have a lifetime warranty. List price is $1,100 and they’re seen throughout the sport. Yet Leupolds are also known as “UPS scopes”. Many return to the factory for reconditioning after 2 - 3 years of hard use, sometimes sooner. Weaver T’s are a little better at holding POA, but their clarity is inconsistent. Some are bright, others aren't. Nightforces and Sightrons straddle the Leups on MSRP and have their pluses and minuses. The Nightforce BR is probably better on tracking, though I’ve heard of a few that wandered. In the 1990’s, Leupold upgraded the old front-parallax 36X with double leaf springs (the earlier models only had one leg per). This helped, but did not lock POA entirely. The original, Leupold BR erector spring:  Now to be honest, the infinitesimal shifts I’m talking about would never be cause for concern on a hunting or semi-precision rifle. It’s just when we move to the hyper-OCD world of benchrest that they matter. To minimize, or eliminate the issue, competitors got creative. One quick way to accomplish this is to freeze the turrets. Bastardized techniques, like JB welding the erector tube, work but won’t be covered here. Sleeving the wave washer is another trick, one which more firmly seats the erector against the beveled shoulder. Gapped at 0.0003”, it can be further tightened with grease. This won’t impede free pivot, but will lower the chance of off-drum movement. Cecil Tucker, Odessa, TX – about 20 years ago, the Tucker conversion emerged. I won’t delve into the details in the interest of time. Briefly, the modification involves installing a small o-ring on the landing surface that locates the erector. It basically fits the inside of the body, snuggly wedging the tube at dead center. Because Leupolds hold the erector against a spherical ledge with a wave spring, it can unload and not return to center after recoil. Tucker’s o-ring makes sure it does. Cecil also adds a plunger compressed coil spring opposite the turrets. Whereas the stock flat spring exerts 7 ft/lbs of force, Tucker’s yields 30; much more robust than the arched gimble design. Tucker-style conversion:  In Part II, I’ll cover Gene Bukys answer to all this, the Hood POA checker, magnification, and an out-of-the box scope heavily influencing the sport. -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by maxim2841 on Sept 24, 2014 21:41:51 GMT -5

![]() look at this design bed! aluminum fittings Attachments:

|

|

|

|

Post by squawberryman on Sept 25, 2014 6:29:24 GMT -5

It's mind numbing at times, particularly the reamer. Lee you stated 80% of the reamers were such and such. Who looked at that page of numbers and lines and thought "If I change this and/or this, it will make for better shots" for the other 20%. And then how do you qualify the changes? Checkered flags or trophies I suppose...

|

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Sept 25, 2014 18:33:39 GMT -5

The differences in reamer specs are small and primarily center around: 1) Freebore - pertinent to the bullet's ogive and length. 60 - 62 grains work best with short throats, usually ~0.030". If you shoot 66 - 68 grains (especially the dual ogive designs) you'll want more. 0.045" - 0.070" is the common range. Matching freebore to the bullet directly impacts precision 2) Base diameter at the 0.200" mark. Tight, as in 0.4395", works the brass less and may preserve primer pockets. And at 60,000 - 70,000 PSI every thou counts. The downside is the case has less room to rebound, causing tough extraction and bolt click after repeated firings. If you run your shots, 0.4402" is ideal. That extra 0.0007", immaterial as it may seem, is just enough to reduce hard lift. So this decision point is all about cycling and would rarely, if ever, show up on paper. 3) Neck diameter - not as critical as it used to be. Lapua brass only requires turning a few thousandths to clean-up. But tradition and decades of tuning drive most to a 0.262". The thicker you go however, the easier it is to maintain neck tension after many reloads. On a 0.262" chamber, ex. 0.0082" per wall, you'll go down a size on the bushing as work-hardening takes hold. Otherwise, neck tension fades. There are other, more subtle variations but they don't supersede these 3. Roundabout way to answer your question, but that's why multiple grinds exist. It really comes down to your shooting style, the bullet, and desired neck tension. Any of these are capable of world class results. Speaking of reamers, mine arrived last week. JGS, live pilot 6 PPC, 1046 grind. The neck was set to 0.264”:  -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by boltlug on Nov 15, 2014 4:44:02 GMT -5

I've been following this build thread closely. Its so informative, it's the reason that I registered at this site. I can't wait to see more. Keep up the excellent work.

|

|

|

|

Post by seancass on Nov 15, 2014 13:46:44 GMT -5

I've been following this build thread closely. Its so informative, it's the reason that I registered at this site. I can't wait to see more. Keep up the excellent work. Welcome to the site! Probably some of the most knowledgeable folks in the shooting world visit this space. Enjoy! |

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Nov 24, 2014 19:39:35 GMT -5

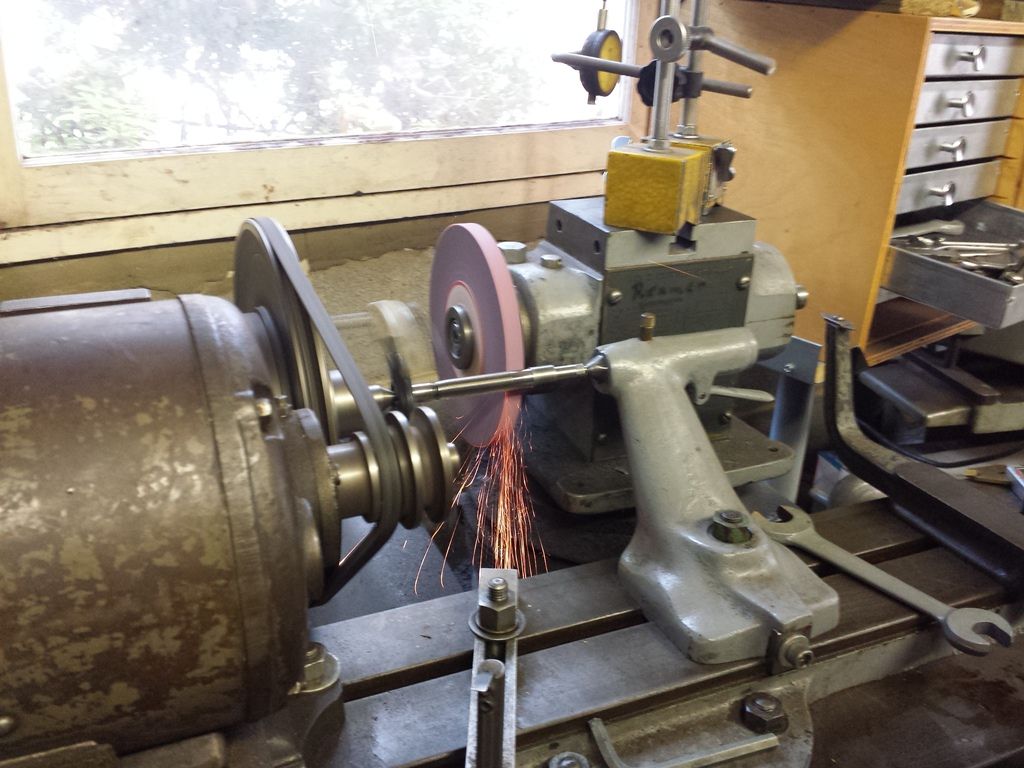

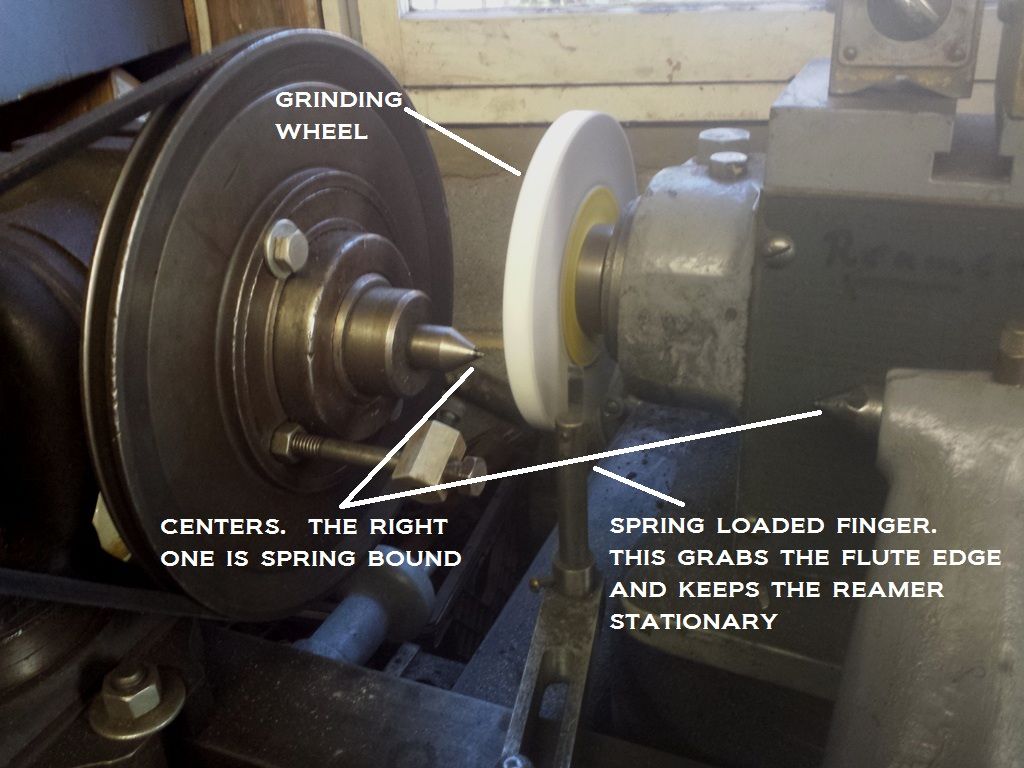

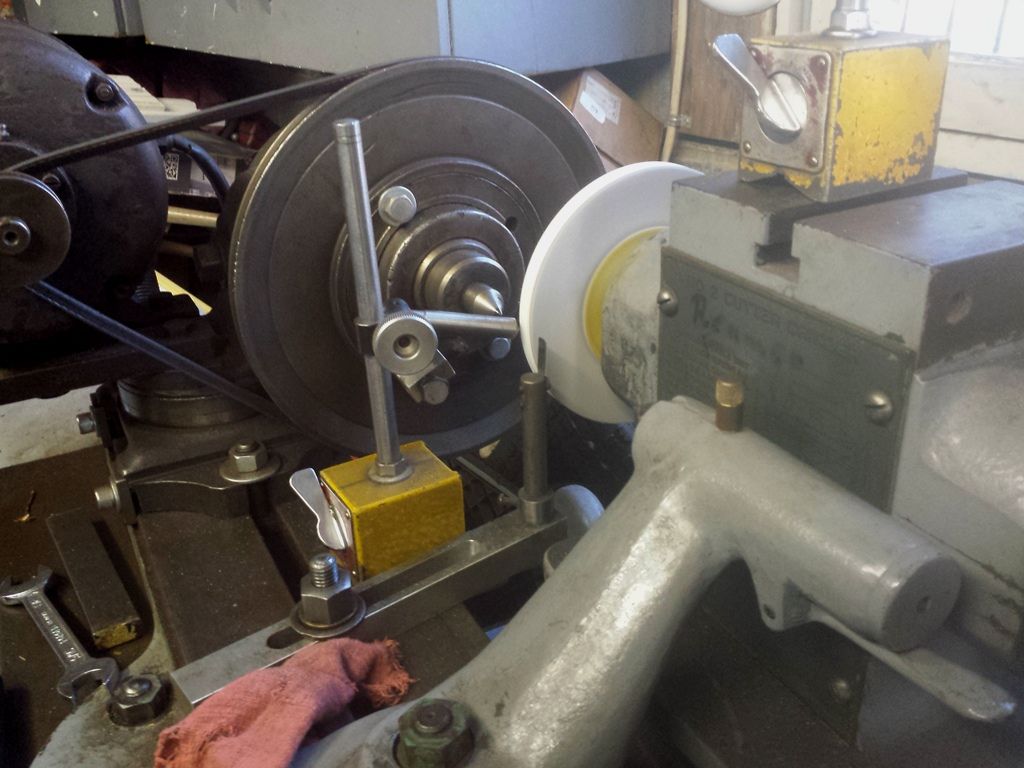

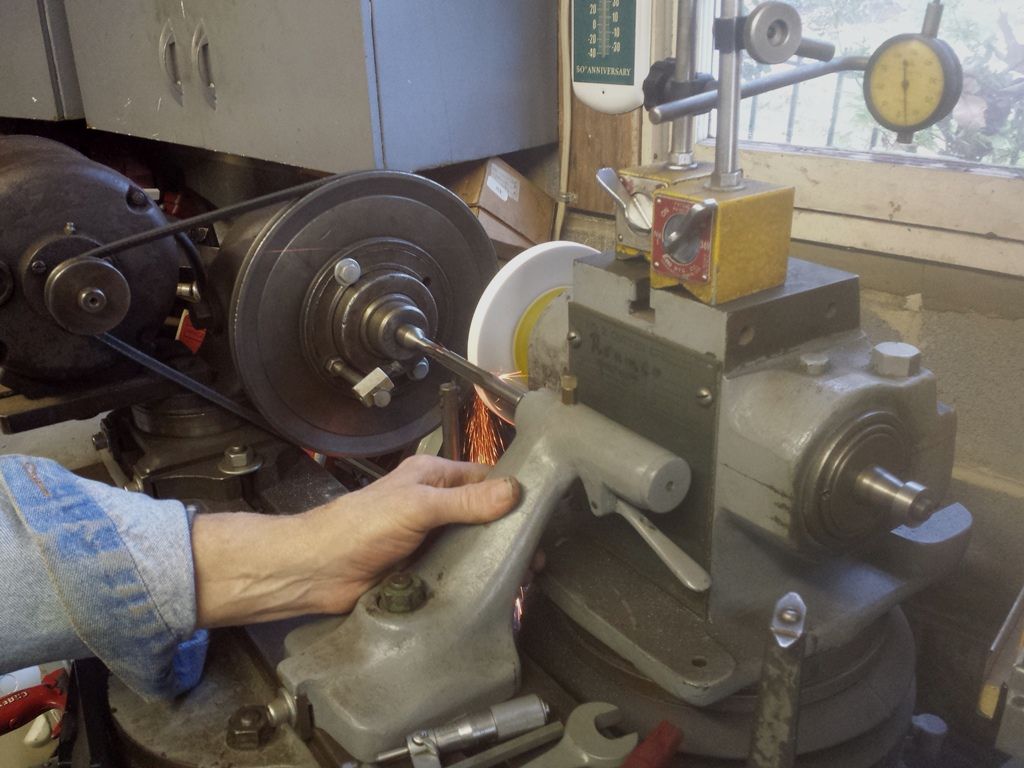

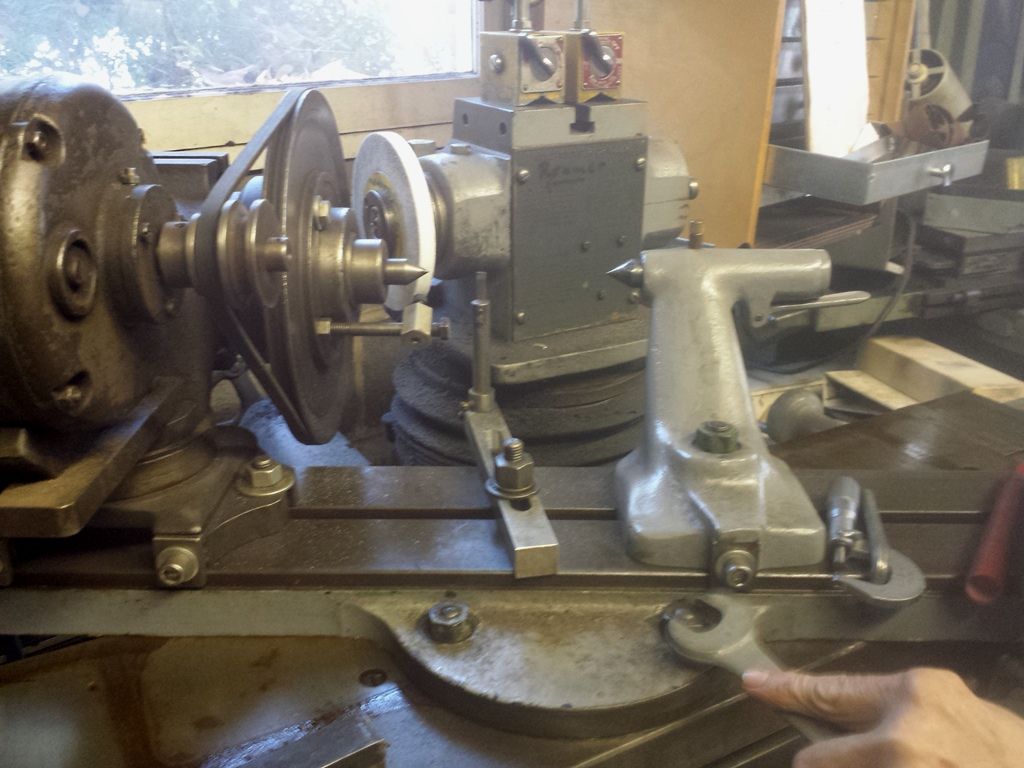

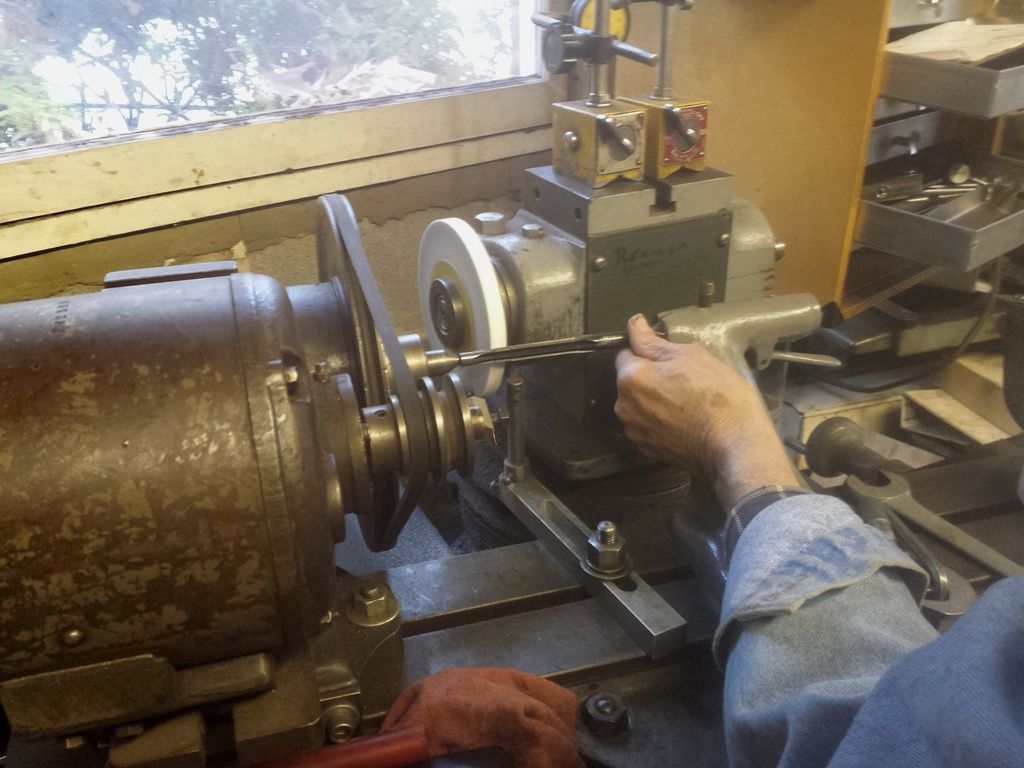

I hoped to document reamer making in this essay. But for the reasons cited above, I went with a commerical JGS. Recently I came across photos and video I took when dad did our .401 Razorback a few years ago (finisher and rougher). I thought it would be relevant to this thread, so here you go. The reamer profiles were turned on a lathe using tool steel. I don't have pictures of that stage however. Cylindrically grinding the bodies on a Cincinnati #2.  Next the flutes are cut on a Brown & Sharpe horizontal mill:  Video of us fluting: Heat treating. The blanks were placed in a furnace and heated to 1,600 F, then oil quenched. Tempering at 400 degrees yields Rockwell 68.   Now it's important to lathe the reamers large enough to overcome warpage. When a narrow piece of steel is heated cherry red and dropped into oil, it'll bend. Not a problem, because the out-of-balance portions are ground out for final dimension. Here are the post-tempered reamers, which Rockwell 68, Notice the ash tone.  The pilots are cylindrically ground to 0.398". We like machining the bores under-size and honing the throats to spec. We don't have digital readout on our grinder, but instead rely on dial indication. This one is accurate to 0.0005".  Grinding the neck. Our first passes are made one-thousandth at time (one thou in on the table equals 0.002" off the diameter).  Front view of the Cincinnati:  The wheel is cleaned and re-trued with a diamond bit:  Main body being ground. Each flute has a down cut, then a relief pass to create the edge:  Video of the first passes on the body. You'll see some flutes are heavy, others are light. This is due to the warpage I mentioned above. On our finisher, the body is 0.468" prior to grinding. The chamber calls for 0.456", so 0.012" had to be taken out. By 0.464", every edge showed a similar amount of bite, meaning run-out was at or under 0.004". The finisher with the neck and body ground. Throats and shoulders still need to be done:  The table is rotated 30 degrees to grind the shoulder:   Lastly, the table is turned to 5 degrees and the lead is made:  The completed rougher and finisher. They're still greasy and covered in marking paint, but they're ready to chamber.  The top one is for the chamber. The lower is the rougher and will be used to make the full-length sizer (done 0.002" under the finisher). -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by Markbo on Nov 29, 2014 17:51:24 GMT -5

That is crazy. What you two do in your shop is difficult for this carpenter to phathom. And you make your own reamers?!?!?!?

That just ... boggles me. As I have said many, many times looking at your work..WOW!

|

|

|

|

Post by maxim2841 on Nov 30, 2014 16:22:52 GMT -5

Lee Martin this is super! What alloy?

|

|