cmillard

.375 Atomic

MOLON LABE

MOLON LABE

Posts: 1,996

|

Post by cmillard on Dec 10, 2021 15:57:18 GMT -5

Great job Lee....you will get what you are after one of these days, just keep after it.

|

|

|

|

Post by longoval on Dec 10, 2021 23:59:02 GMT -5

Varmint for score is such a cool concept.

I have never competed in it as I have neither the skills nor equipment. But at my local range they sell a number of targets (in addition to letting you bring your own); one is a 300 yard VFS IBS target. Kinda random because this range only extends to 200 yards.

I often buy these targets and shoot informally at 200 or even 100 yards. The dot is huge on my 300 yard targets compared to the 100 yard version. Still I'm doing well to mark 3/5 of the dots.

Going 25/25 on properly sized targets at a sanctioned event would be an INCREDIBLE feat. At least in my eyes. But so is 24/25.

|

|

|

|

Post by starmetal47 on Dec 11, 2021 11:23:14 GMT -5

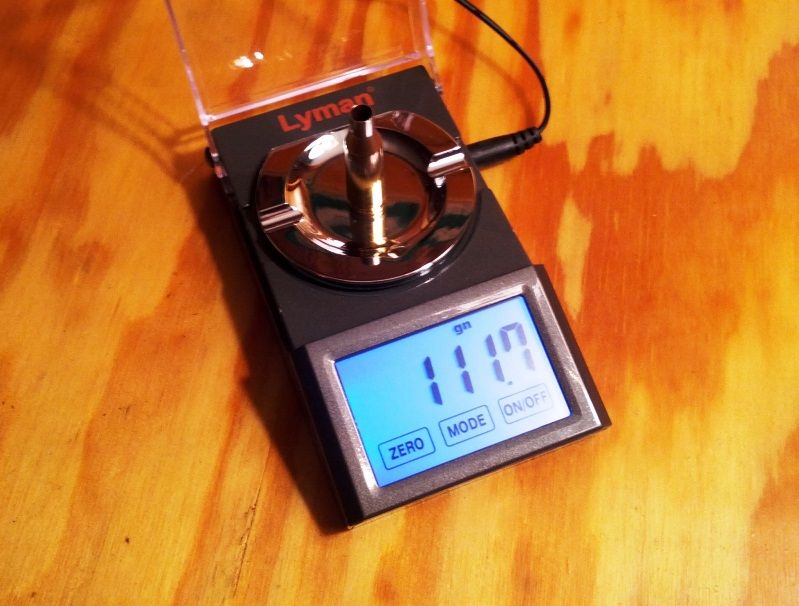

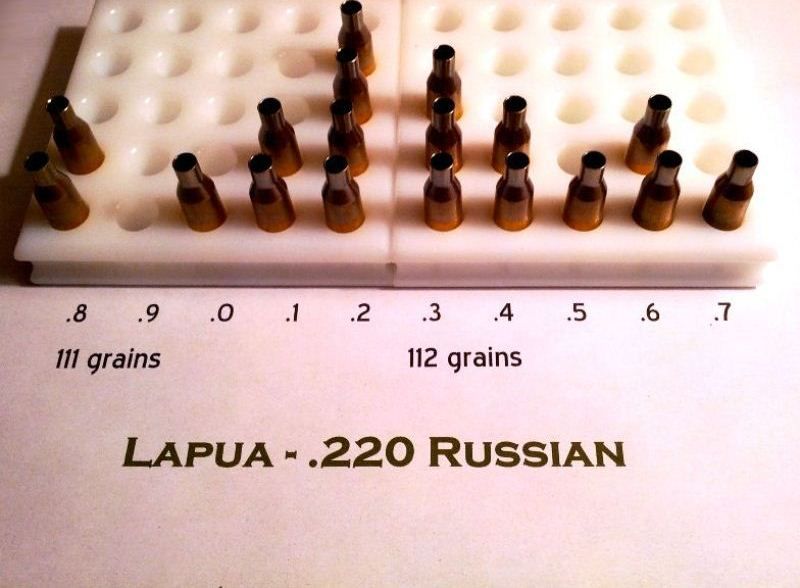

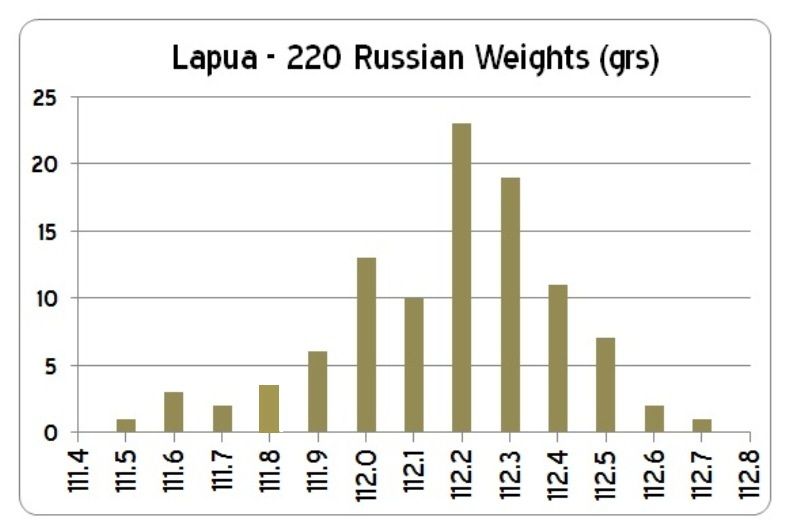

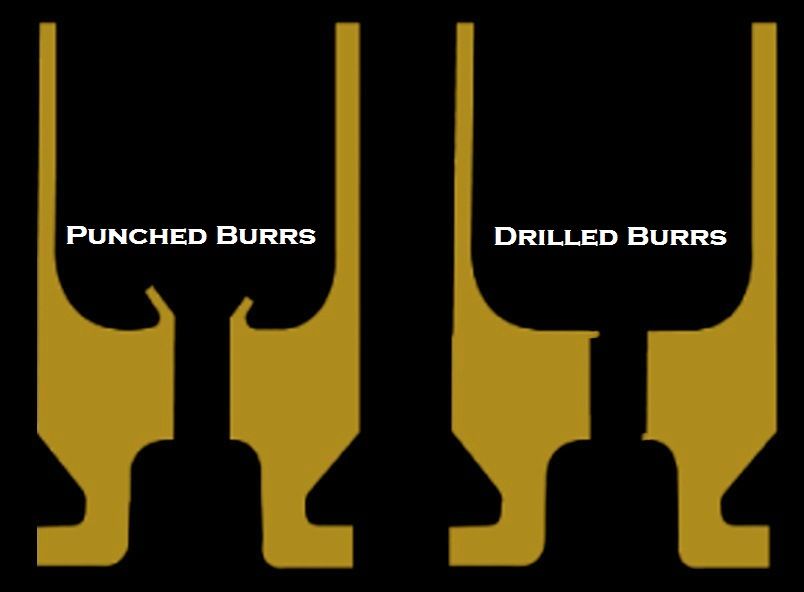

Step 2 – The Parent Brass It’s important to align our proposed chamber specs with the real thing. Production variability exists, even within the same make of brass. So never trust a dimension sheet when cutting reamers; the parent must be measured and it’s better to do so across a wide sample. Fortunately we’re using Lapua and their boxes are marked with lot numbers. 200 pieces of new 220 Russian were ordered at just under $1.00 per. They’re the universal foundation for 6 PPC forming and have no equal when it comes to quality.    One box was inspected in total for the following: 1) Base diameter 2) Case weight 3) Neck concentricity 4) Shoulder run-out 5) Primer pocket depth 6) Flash hole uniformity The base diameter above the extractor groove ran consistently 0.4395”. My reamer transitions to 0.440” just 0.200” from this point so we’re good on the web. Segregating brass by weight is widely debated. Some say it accurately depicts case volume if the external dimensions run true. Others say it’s a “nit” process that can’t be quantifiably tied to smaller groups. If you have an electronic scale, and most benchresters should, why not? The step doesn’t cost anything and it mitigates another variable. I think it can add value, especially when there’s deviation within a small quantity, say 50 – 100 pieces. I once weighed forty Remington 264 Win Mags, all new and all from the same lot. To my surprise they showed an 11% spread (196 - 221 grains). One box of new 220 Russian was scaled and they fell between 111.5 and 112.7 grains. That’s a 1% delta but if you exclude the outliers it pinches to 111.9 - 112.5...a miniscule six-tenths of 1%. That’s insanely low, even for the highest grade of brass. My little experiment confirmed what many have said about Lapua hulls. Their QA is so high there’s no need to segregate. I played it safe however and paired the 112.1 – 112.2 and the 112.3 – 112.4 batches.  Processing the box  Final distribution  Neck and shoulder concentricity were measured using a Sinclair gauge. The neck run-out averaged a half-thousandth while the shoulder never exceeded 0.001”.  PPCs use small rifle primers which mic 0.121” in height. Ideally you want the cap to seat a little below flush, say 0.002 – 0.003”. For that reason a lot of guys ream the pockets to achieve this spec. Using a depth gauge mine averaged 0.123” so there’s no need to recut them. Now dozens of benchrest articles have been written about flash-hole diameter, edge consistency, and uniformity. Back in the 1970’s Palmisano and Pindell funded a few trials to determine the ideal size. They landed on 0.059” which is less than the standard 1/16” (0.0625”) de-capping pin. Since we’ll be making our own die I can install the correct diameter. We sampled a few pockets under magnification and the Lapua flash-holes are dead on. Small brass flakes or obstructions are common around the hole itself. Unlike domestic brass which is punched, European brands such as Norma and Lapua drill the throughway. While the latter tends to produce a cleaner passage small burrs can result. To eliminate them you’ll need a pin vise and a 1.5mm drill bit (0.0595”). Through very slow hand reaming they’ll true without up-sizing.   -Lee www.singleactions.com"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time" A benchrest shooting acquaintance of mine feels a better way to sort cases for best consistency is by internal volume measurements. It's a proven fact in case manufacturing the larger weight inconsistency is when they machine the extrator groove and rim. He shrunk his groups a very noticeable bit by sorting by weight volume. I would like to see you do a test between weight and internal volume sorting. |

|

|

|

Post by bradshaw on Dec 11, 2021 13:05:07 GMT -5

starmetal.... I would not challenge Lee Martin’s road to accuracy.

I watched shooters in handgun silhouette take meticulous steps to to increase accuracy, when the individual wasn’t close to outshooting the gun. Lee is exceptionally set on eliminating mechanical variable, where he can, to build accuracy. A feature of squaring away your gear is to remove from the mind all doubt of equipment. Simpleminded as sharpshooting is, it is performance which admits no distraction.

Lapua brass made for handloading is just that: made to HANDLOAD, with the knowledge it will be LOADED & RE-loaded, all in mind of performance. Handloaders may not want to hear this, but much commercial brass is made to contain a factory loaded round, with no consideration given to reloading. Even so, some factory brass is exceptional. Federal Cartridge Company muscled itself to numerous podiums through the 1970’s and 80’s, cementing a reputation earned on the Firing Line only.

In my own loading of revolver ammo for competition at the highest level, I did not weigh brass, nor measure volume. Seriously doubt I could have accurately measured case volume. BULLET PULL of the size case became a prime separator of brass, with a strong grip of the seated bullet selected for competition and hunting.

7mm/308x1-3/4” brass which set the 80x80 Record was not weighed. It was formed from one batch of military arsenal .308 (7.62x51mm). As Lee Martin infers, absence of shoulder runout and neck runout are vital to accuracy. Compared with Handgun Silhouette, Bench Rest accuracy is rocket science. Respective accuracy required of the two disciplines barely shares the same planet. Yet my crude bottleneck Unlimited pistols occasionally printed 1-inch groups @ 200 meters (219 yards). Competition offers the advantage of WITNESSED SHOOTING.

Firearm before Ammunition

Gun before bullet in the world of accuracy. Only the firearm proves the accuracy of a load. CASE VOLUME by itself plays no part in BULLET ALIGNMENT. The less jumping across tracks a bullet has to do between chamber and muzzle, the better its chance to fly straight.

Numbers

If we could dispense with atmosphere and the human on the trigger, we could reduce accuracy to numbers----measurement. The atmosphere factor and the human factor pollute the equation. Nevertheless, we are able to discern the importance of dimensions. Some dimensions are more important than others. And then there is the ORCHESTRA of DIMENSIONS (which is how I describe REVOLVER ACCURACY). I have an emotional investment is seeing Lee Martin shoot well. Lee has done a masterful job of BUILDING ACCURACY.

David Bradshaw

|

|

|

|

Post by starmetal47 on Dec 11, 2021 15:56:15 GMT -5

Dave here is what I base it on. At the Hornady case manufacturing line they pulled some cases off the line before the extractor groove and rim were cut. They were amazingly consistent in weight. In other words the cases were finished except for what I just mentioned. I believe the weight variance was to the right of decimal point as I don't remember the exact number. Then they pulled cases off the end of the line totally finished. The weight variance went to the left of the decimal point. Alright, keeping that in mind, David Tubbs for one measures the wall thickness's of the case. I believe he my use the NECO tool for that. Talking the wall not the neck thickness. He sorts by that. What I'd like to see/hear from Lee Martin is measure with his weight checks and also the volume and see how they compare. I''d also like him to shoot for accuracy with his case weight check and then shoot to his volume check and see how much difference there is. I'm not diputing Mr Martin's knowledge and shooting one iota. I'm trying to learn and being he's professional at shooting for accuracy I would like see what he says. I knew of man that took 308 cases and expanded them out straight. Then he turned the case wall thicknesses to a consistant thickness around the circumference of the case. Don't ask me how he done all this as I don't know. Then he formed it back to the bottleneck configuration. Said his accuracy improved. What he done, if you think about it, is made the interal volume consistent. Tubbs believes, or maybe proved, that inconsistent wall thickness ruins accaracy. He also said that the cases with inconsitent wall thickness whip like a banana when fired in the chamber. So here's what we're dealing with: Weight consistency, internal volume consistency, and case wall thickness consistency. Do some shooters do all three? I'd like both your and Mr Martin's input on this. BTW I know that Lapua brass is exceptionally good brass in all respects.

|

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Dec 11, 2021 16:28:16 GMT -5

Starmetal47 - thanks for taking an interest in this thread. When I started out 8 years ago, I got wrapped around a lot of little things like sorting cases by weight. I must admit, I haven't done that since my first batch of 6 PPC. Now, I take cases from the same lot, expand the necks on a mandrel, neck turn, verify neck wall thickness with a tube mic, fire-form, then trim to final length. Benchrest has hundreds of nit things that'll drive even the most OCD person nuts. I've found a lot of those things contribute to top precision / accuracy. Some not so much. Most of which are covered in the previous 65 pages. I will say this however.....to shoot towards the top you have to have these four: 1) The ability to read wind and hold-off 2) The ability to tune your rifle and keep it in tune as conditions change 3) A good barrel 4) Great bullets that mesh well with that good barrel. Fall short on any of those four and you'll be middle of the pack or lower. There's no action, reloading trick, bedding job, front rest / rear bag, scope, trigger, etc, etc, that'll make up the difference. BTW, David mentioned bullet pull. I feel my shooting improved one I began annealing after every firing. It's hard to prove how much it helped, but I am doing better at 200 & 300 yards annealed. -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by starmetal47 on Dec 11, 2021 16:58:20 GMT -5

Thanks for welcoming me to this thread Lee. On some of the cast shooting forums they always have the question "how do you prepare your brass". Almost 100 percent of the time they are shooting standard sporting rifles, maybe a few varminters and heavy barreled rifle, and most often milsurps of all flavors. Me and my pardner in that type of shooting with those aforementioned firearm tell them when they mention all the benchrest techniques that they are wasting their time for those types of firearms. We have also mentioned, like you have, you have to be able to shoot and you have to have excellent cast cast bullets. Thanks for your reply.

|

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Jan 11, 2022 19:23:11 GMT -5

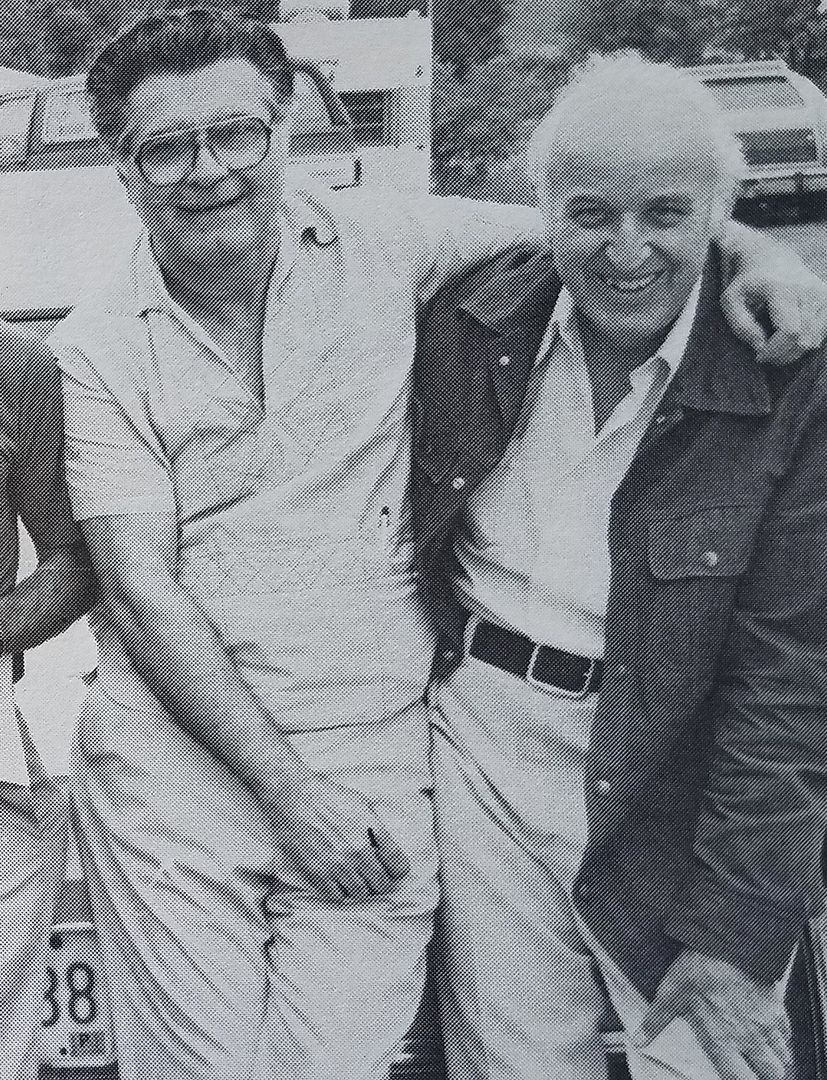

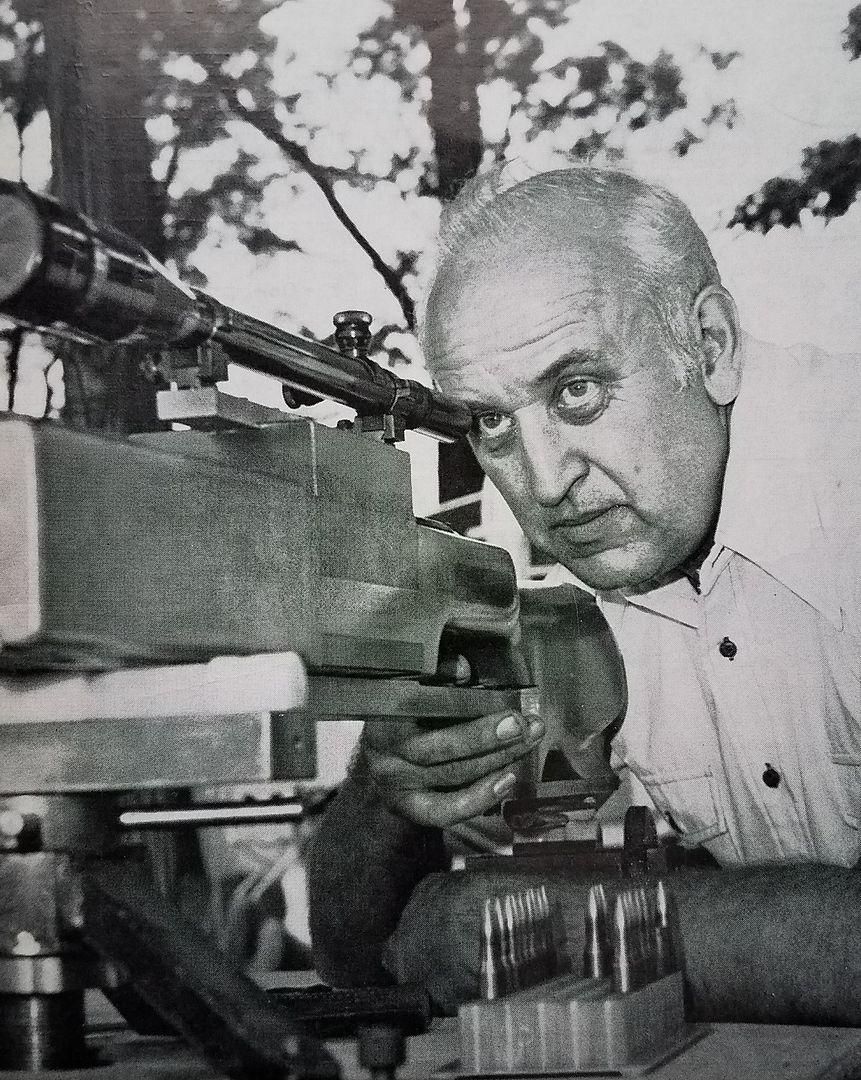

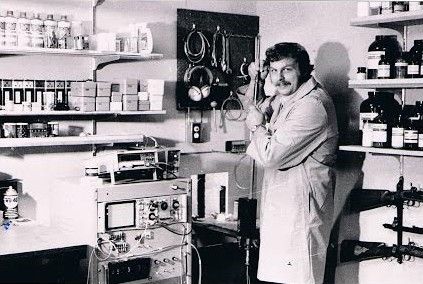

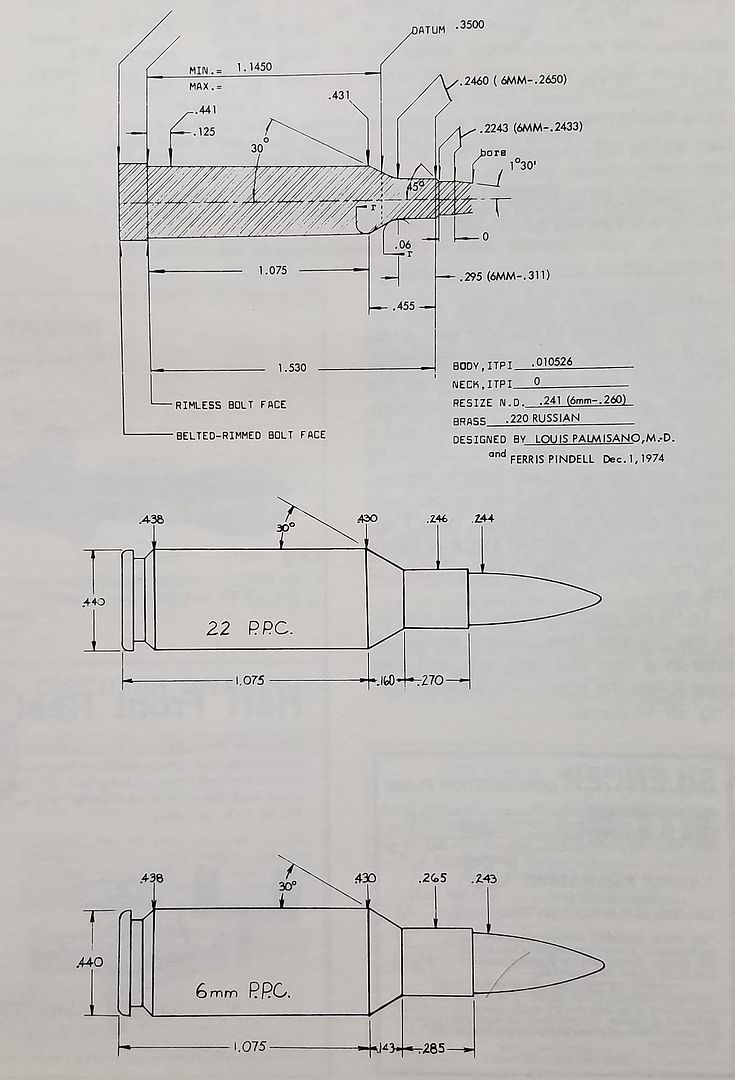

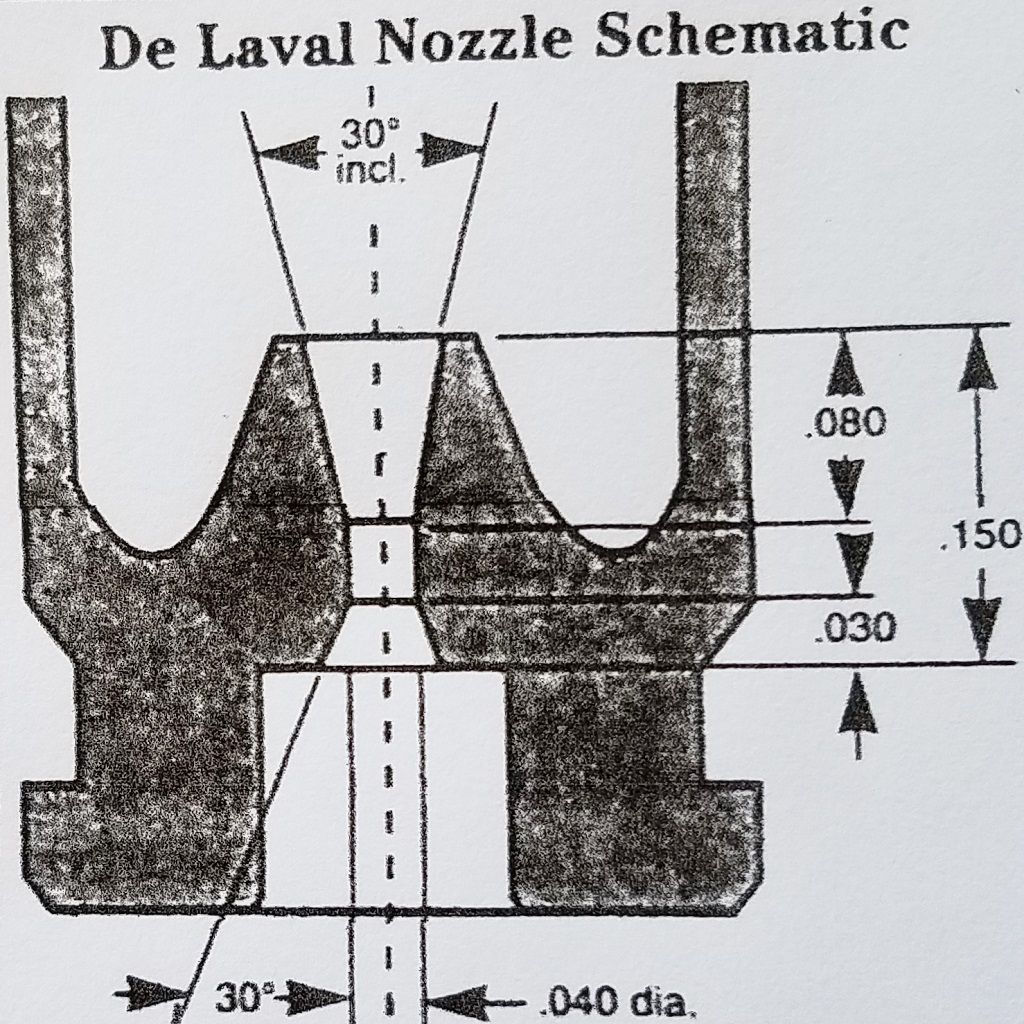

Back in 2018, I did a two-part article on the origins of the PPC cartridge. Both were published in Precision Rifleman magazine. I thought I'd include them in this thread for those that may be interested. _______________________________________________________________________________________ PPC Origins – Part 1 by Lee Martin In the early 1970’s, Dr. Lou Palmisano and Ferris Pindell took a ground up approach to improving benchrest case design. Their efforts gave us the Palmisano & Pindell Cartridge, commonly known as the PPC. It quickly dominated short-range competition and to this day nothing has come close to supplanting it. Veteran benchresters know most of the history behind the PPC’s development. The younger crowd perhaps has a grasp of the condensed story. In between those ends is a lot of theory, experimentation, and capital investment. This two-part article delves into the how and why of the PPC. The majority of what I’ll share comes straight from Palmisano & Pindell’s working papers. Some of this material has been published, other portions have not. Lou Palmisano was an avid precision shooter and became intrigued with cartridge design in the 1960’s. He firmly held that shorter cartridges offered more consistent ignition, and hence better accuracy than longer profiles. According to Palmisano, shorter cases have four distinct advantages: • Lower ratio of charge height to charge diameter • More complete powder consumption • Less muzzle disturbance, and thus more consistent barrel harmonics • Uniform ignition pattern He skipped the .219 Donaldson Wasp in his early trials. The wildcat had already been replaced, or as some would say ‘bested’, by the .222 Remington and 6 x 47. Instead, Palmisano worked with the .220 Swift hull. He was not the first. In the 1940’s, Al Bar created his .220 Baby Swift. This was nothing more than a 1.50” version of the parent with slight shoulder modification. The cartridge was written-up by Richard Simmons in “Wildcat Cartridges”, 1947. Like Bar, Palmisano found the short Swift laborious to form. Case splitting plagued him as did signs of erratic pressure. Around the same time, H.L. Culver necked his Swift based .25 Dart to 6mm and shortened it to 1.50”. It never caught on, though Culver shot it competitively. I reference it here only to illustrate that a few benchrest shooters liked the 0.440”-ish x 1.50” boiler. However, Frank Barnes’ 308 x 1.5 probably did more to solidify the short & fat craze than any other wildcat. Many 308 x 1.5” variants emerged during that era, the most notable being Jim Stekl’s .22 BR. It became the foundation for the 6mm BR, which would appear in the late 1970’s. Ferris Pindell also spent many years working with 308 x 1.5” wildcats. And this is a vital piece of the PPC’s history. Its underpinning was most certainly laid in the 1960’s. Granted, Pindell and Palmisano used different parent cases and operated hundreds of miles apart. That didn’t matter. It was their shared vision and desire to build a better mousetrap that put them on the same path (unbeknownst to one another). Eventually their paths crossed and competitive benchrest was forever changed. The .220 Russian, from which the PPC is based, was not a common cartridge in the 1970s. It came into the United States thanks to Sako of Finland. At the 1962 World Shooting Championships in Cairo, the Russians shot 7.62 x 39 necked to .22-caliber. Sako later marketed it as “.220 Russian”, yet North American distribution was thin. Fred Davis tested a so-chambered varmint rifle for Guns Magazine in 1969. He reported fine accuracy but believed it would do even better expanded to 6mm. Davis implied the short-stubby shape may be tad over-bore in twenty-two. To my knowledge, he never wildcatted the Russian, likely due to its scarcity. Then in 1971, Larry Sterrett covered the .220 Russian in Handloader Magazine and that caught Palmisano’s eye. With minor body and shoulder modification, case capacity would be near ideal for .22 and 6mm. Equally important, Sako produced it boxer primed with small rifle pockets. Lou immediately wrote Sako in an attempt to purchase the brass. But before they could respond, fate intervened. One day, Palmisano was shooting with long-time friend Joe Broggi. After lunch, they visited a local gun store to browse. Before leaving, Joe called Lou over to see five dusty ammo boxes. Low and behold, they were .220 Russian. Two weeks later, Palmisano took some of it to the 1974 Super Shoot in Wapwollopen, PA. What followed was the proverbial meeting of the minds. Quoting Dr. Palmisano: “I showed the case to a number of the world’s most prominent and knowledgeable precision shooting ‘experts’. Except for Ferris, they cavalierly dismissed the case as just another wildcat. In looking back on it, one has to wonder at those mysterious ways that determine fateful happenings. With so many prestigious men, all with many years experience, showing no interest at all….’The .222 is it’, ‘Everything’s been tried and nothing beats the deuce’, ‘You’re spinning your wheels Doc’, etc, etc”. I might very well have thrown in the towel except for Ferris Pindell’s enthusiasm. We were confident the .220 Russian case by Sako was what we needed”. Dr. Lou Palmisano & Ferris Pindell:  Ferris Pindell at the bench:  The two defined five main goals for their new wildcat. First, no cartridge can perform an infinite number of tasks. Their basic quest was supreme accuracy out to 300 yards. Second, the shape of the case, and subsequently the shape of the powder charge, are paramount. Third, complete consumption of the powder after uniform ignition is a must. Fourth, low muzzle disturbance and consistent barrel vibration shot-to-shot is intrinsically tied to accuracy. Fifth, the optimum velocity for short-range .22 and 6mm bullets is 3,200 – 3,400 fps. Pindell’s technical acumen had an immediate impact on the PPC’s development. He started competing in benchrest in 1946 and knew the sport well. Ferris was also an accomplished tool and die maker, having been employed at Sierra bullets. When he moved back to his native Indiana, Pindell formed his own precision tooling company. Select clients included Winchester, Remington, and Super-Vel, for which he made bulleting swages, dies, and punches. The first thing they assessed was Sako’s .220 brass. While the dimensions were a hit, the hardness was not. Both Pindell and Palmisano knew it was too soft. Moreover, there was too much case weight variation to roll match-grade ammunition. They wrote Sako asking for two improvements: 1) Draw the cups from 70-30 brass with a Rockwell B rating of 79 – 80, and 2) Drill, not punch, the flash holes 0.066” diameter. Sako agreed to the changes, leaving Pindell and Palmisano to focus on the case profile. They began by ordering a standard .220 Russian reamer from Keith Francis. A .22-caliber Atkinson barrel with 1:14” twist was chambered and fit to an Unlimited Class rifle. Test groups were very small and amazingly consistent. The two knew they were on to something. To their credit, they didn’t stop there. Even though the .220 Russian seemingly out-performed the Deuce, they pushed the envelope. In December 1974, six more barrels were chambered in .22 and 6mm derivations of the Russian. Each differed in shoulder angle and body taper. Palmisano and Pindell did not specify all the tapers used, but shoulder angles were set at 30, 35, and 40 degrees. Those barrels were shipped to Pawlak Laboratories in Issaquah, Washington where rigorous testing ensued. Dan Pawlak opened Pawlak Laboratories in the early 1970’s after renting a Vietnam War-era plant. Located 3,000 feet up on Issaquah’s Taylor Mountain, it was the perfect place to conduct ballistic research. The young chemist quickly struck it big by creating Pyrodex powder. Hodgdon bought the rights to distribute it and muzzle loaders have been in heaven ever since. Tragically, Dan Pawlak and three others were killed when the facility exploded on January 27, 1977. As you’ll soon see, Dan was active in the PPC’s design from 1974 – 1975. Pindell and Palmisano hoped to evaluate other variables, but Pawlak’s untimely death shelved those plans. With six barrels and a good supply of brass, Pawlak began testing in January 1975. Five major factors were studied – pressure, velocity, barrel vibration, peak pressure, and muzzle disturbance. He provided his initial findings in a letter to Lou Palmisano dated May 6, 1975. Rather than paraphrase, I’ll share Pawlak’s exact words: “Dear Dr. Palmisano, Enclosed is the data you requested excluding flash hole enlargement which will be forthcoming. I gave you my worksheets because I felt you were anxious to receive the results. The cartridge is very interesting. It has good pressure capability in spite of its short length, being able to handle 65,000 psi peak pressure without any permanent deformation. The particular geometry of this case coupled with the small rifle primer caused relatively slow (approximately 25% slower) rise times as compared to the .222. This may or may not be beneficial to accuracy. Slower rise times are frequently accompanied by better consistency and of course that would be beneficial.Hodgdon’s H322 would be my first choice of propellant from an internal ballistics point of view. It can be loaded to 100% loading density in both calibers and give almost identical curve profiles in both. Second choice would be IMR 4198 but it will not meter accurately. Reloader 7 does not appeal to me at all, especially after I blew the head off a .222 with it while testing for you. You can see the last of the trace coming jaggedly down on the .222 graph.Third choice would be W748 as it is the most efficient powder tested giving high velocity with low pressure. It might be interesting to try other ball powders with a more suitable burn rate exponent. Because of the very limited testing I have done with this cartridge, my observations must remain general. However, these curves should give you the basis for further experimentation of your own. If you have any further questions, please contact me. Best regards, Dan Pawlak” Dan Pawlak in the lab:  It quickly began apparent one configuration was superior across the five factors tested. In the spring of 1975, reamers for the final design were ordered from Keith Francis. The PPC was defined as follows: • Overall length = 1.500” • Body taper = 0.010” per inch • Shoulder angle = 30 degrees • Flash hole diameter = 0.066” Internal volume equaled 33.8 grs of water, compared to 27.5 grs for the .222 Remington and 31.7 grs for the .222 Remington Magnum. Eventually, the flash hole diameter was further reduced. It’s debatable whether the current 0.059” – 0.062” offers any accuracy advantage over the original 0.066”. Pindell and Palmisano had plenty of more questions for Dan Pawlak. I’ll cover those along with the PPC’s first major benchrest victory in Part II. That victory occurred just three weeks after Pawlak’s May 9th letter. Things were moving fast. The original PPC reamer prints:  -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Jan 11, 2022 19:26:29 GMT -5

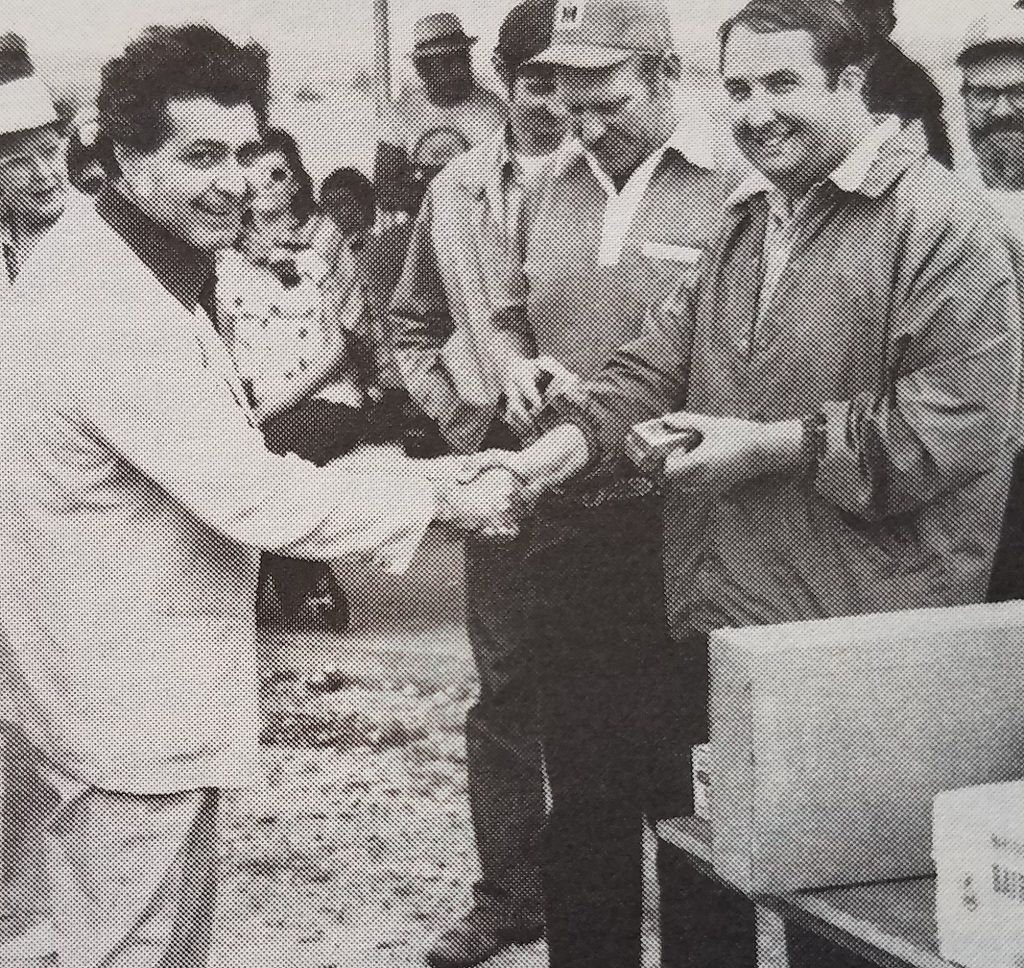

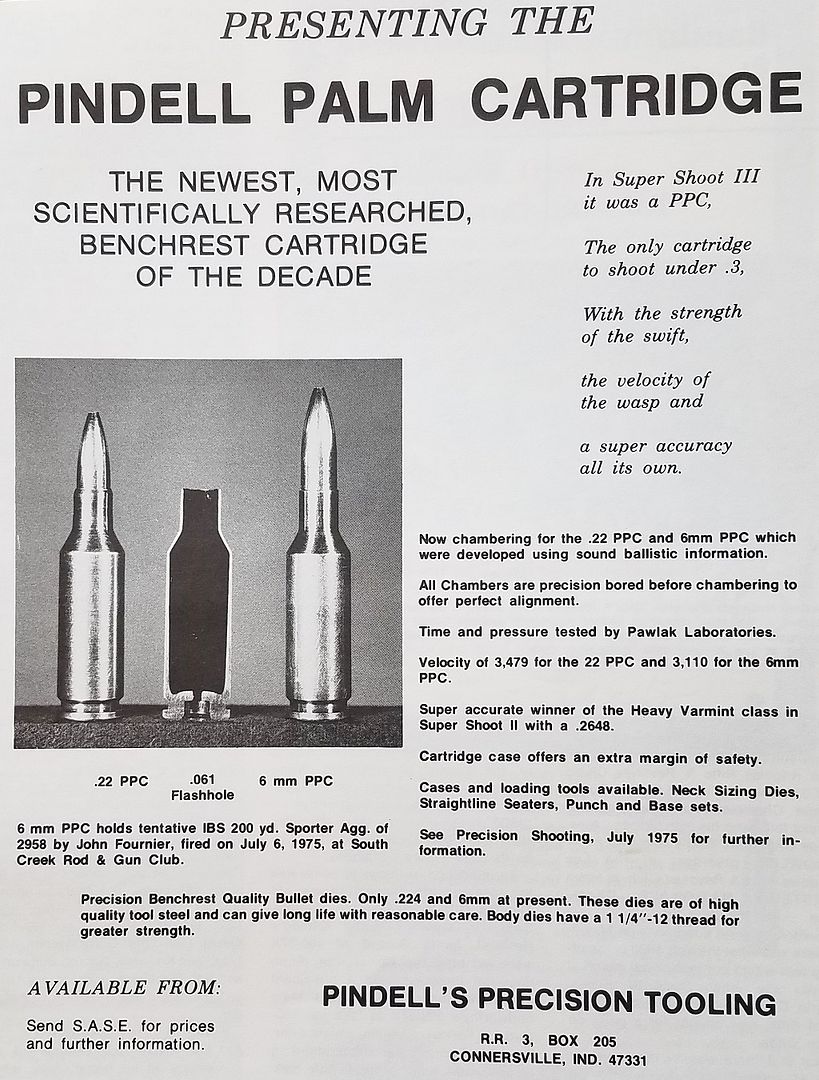

PPC Origins – Part 2 by Lee Martin Part I of “PPC Origins” left off at May 1975. Pawlak Laboratories had tested a variety of powders in .22 and 6mm barrels. The parent case’s shoulder angle and body taper were altered to assess five factors - pressure, velocity, barrel vibration, peak pressure, and muzzle disturbance. Palmisano and Pindell used that feedback to solidify the PPC’s dimensions. To recap: • Overall length = 1.500” • Body taper = 0.010” per inch • Shoulder angle = 30 degrees • Flash hole diameter = 0.066” In late May 1975, the two each took a pair of PPC rifles to the Super Shoot in Midland, TX. The cartridge was laboratory vetted, but how would it fair against wind, mirage, and changing air? Lou Palmisano answered that with a resounding win in heavy varmint-100. Through tricky conditions, he steered his .22 PPC to a low 0.2648” aggregate (0.341”, 0.313”, 0.213”, 0.295”, and 0.162” – the load was 24.0 of 4198). Ron Prachyl took second place with a 0.3002”. The running joke was, “It must be the cartridge. We all know Lou isn’t that good a shooter”. Three months later at the New York State Championships, John Fournier won heavy varmint and got second place in LV shooting a 6 PPC. Mike Walker edged him out for the two-gun win. The PPC again shocked the benchrest ranks in August 1976, when Lou’s 14-year old son won the 200-yard leg at Johnston, NY. David Palmisano ousted 180 competitors with a 0.3280” agg. If people hadn’t taken notice to that point, they were starting to. It would take more time before the cartridge totally dominated short-range BR, but the seed was planted. One by one, top shooters were transitioning from 222’s and 6x47’s to the PPC. Myles Hollister was an early adopter and famed gunsmith Roy Vail placed high praise on the wildcat. Dr. Lou Palmisano receiving one of his many awards:  14 year old David Palmisano after winning at Johnstown:  The PPC was commercialized with a full-page ad in Precision Shooting, August 1975. They touted it as: “The newest, most scientifically researched benchrest cartridge of the decade. In the Super Shoot, it was the PPC; the only cartridge under 0.3”. With the strength of the Swift, the velocities of the Wasp, and super accuracy all its own”. The original PPC ad from 1975:  Forty plus years later, it’s hard to argue with these claims. Palmisano and Pindell supplied barrels, loading data, precision reloading dies, and bullet swaging tools. In essence, they gave the sport everything they needed to cut over to the PPC. For their efforts, Lou Palmisano was named the 1976 Benchrest Person of the Year. Lou received the award at the Super Shoot and he was quick to give equal credit to Ferris Pindell. Honorable mention went to Dan Pawlak and the late Bob Hart. Both were ardent supporters of the PPC. In one year, the PPC went from a brainstorming session at Wapwollopen to a full-fledged competitive offering. Pawlak Laboratories continued their evaluations beyond the 1975 SS victory. Lou and Ferris were not about to rest on their early success. Perhaps the most insightful report came from Pawlak in June 1975. In a letter dated June 11, he conveyed the following: “After completing further tests of your .220 PPC we have made more striking observations. We began running statistical analyses on pressure time curves with 24 grs of IMR 4198 and the 53 gr Hornady H.P. We were concerned with the outcome of our calculations which showed that the bullet was exiting the muzzle long after the relative peak velocity had been reached. To prove the correctness of our data we installed a sensor at the muzzle to show precisely when the bullet left in relation to the pressure curve. This test proved our data to be accurate (neglecting friction). What this shows is that the bullet is leaving the barrel some 640 microseconds after the peak pressure had been reached leaving only an approximate 8,000 PSI breech pressure. This is a very low value indicating complete consumption of the propellant and a very low muzzle disturbance. We will be able to approximate the muzzle pressure by installing a second transducer near the muzzle where three pressure characteristics are involved – static, dynamic, and stow. Although we have not tested the .222 in a similar manner, I would extend a guess that this is a unique phenomenon of the .220 cartridge design. The extended volume of this design is far superior to the .220 Russian in that a large volume/small bullet diameter combination allows less volume sensitivity to bullet movement. This is enhanced by the short L over D and the shallow taper of the case. True, there have been other attempts along this line, i.e. .17 Bee, .224 ICL, 6mm Donaldson International, etc., yet none of these has coupled the short, fat shape with a small primer and even smaller flash hole which is not obvious. In fact, it has been the effort of primer manufacturers to fill an individual cartridge with as much hot particles as possible. This work is clearly documented by nearly every work on the subject. You have perhaps one of the more revolutionary concepts of internal ballistics to come about. The fact that the pressure curves are consistent in shape attests to the efficiency of the system. A theory might be that the small flash hole regulates the flow of hot particles and gases into the case over an extended period of time. More experimentation along this line would be in order. The benefits of having the ignition properties regulated are immediately obvious; dependence upon very uniform primers is somewhat alleviated and there is a longer duration for heat transfer to the propellant. The same is true of having a late bullet exit; velocity uniformity need not depend so much on uniform pressure profiles. If the propellant weight is consistent and neck tension is negligible then the velocity will tend to be uniform because most of the potential energy available to the bullet will have been imparted to it long before it leaves the barrel. Mr. Roland Franzen, who assisted in the test and who is past head of the instrumentation department at Diehl in Nurnberg, West Germany for 10 years (Diehl is a military munitions plant employing 14,000 workers) was quite taken with the efficiency of the cartridge. He stated that the 7.62 Nato (.308 Win) round, a sort of standard of the industry, had a great deal of muzzle pressure and in fact all small arms rounds he had ever tested had similar characteristics. You of course have proven the .220 PPC’s inherent accuracy. We have begun tooling up for the vibration tests. Mr. Franzen estimated the first harmonic will attain 2000 Hz. When this value is measured we will be able to find the wave lengths in each barrel so tested. Of course we will directly measure the amplitude of the muzzle whip and its relation to the bullet travel. The significance of this cartridge design is surely underestimated. Its potential as a military round should not be overlooked. – Dan Pawlak” Dr. Lou Palmisano at the 1976 Super Shoot:  This further illustrates the rigorous testing applied to the PPC. In later correspondence, Pawlak confirmed his suspicions on harmonics and whip. The cartridge did exhibit less muzzle vibration than other precision rounds, particularly at bullet exit. This prompted Pindell to hypothesize more about the shape of the flash hole. Leveraging the De Laval passage used in rockets, he believed better ignition could be had via a cone entrance, short cylinder, cone exit contour. This would increase the mass flow of propellant gases in a given chamber. Dan Pawlak agreed with Pindell and took the notion a step further: “Although all the present mathematical formulas apply, rocket nozzles have been designed for use at atmospheric pressure and below, with chamber pressures reaching a maximum of around 3,000 PSI. Whereas the chamber pressures may vary greatly during combustion, the exit pressure remains relatively constant. In a cartridge case the gases are exiting into a fixed volume which will increase pressure first with the primer gases and secondly with the combustion of the propellant in the chamber. The time factors here are very short and it would be my observation that for the first part of primer combustion that the De Lavel effect would be of value by increasing the particle velocity into the propellant granules. By decreasing the throat diameter and increasing the exit area this can be enhanced, perhaps to the point where the gases bore a hole into the propellant grains before they begin combusting. – Dan Pawlak” Original drawing of Pindell's De Laval nozzle:  This was pretty heady stuff. Beyond reshaping the flash hole, they considered inserting cordite rods, painted with a wet mix of priming compound over the De Laval nozzle. The goal was to achieve more uniform ignition top-to-bottom. I don’t know if the rod theory ever left paper. Lou Palmisano hinted that had Pawlak not died, the priming rods would’ve been pursued. That leads me to think it was never attempted. But the idea alone demonstrates their willingness to defy convention. Lou Palmisano tried to get the gun industry to adopt the PPC. The first inroad was almost forged when Roy Vail showed John Olin, chairman of Winchester’s parent company, the .22 and 6mm PPCs. Olin saw their potential and asked Pindell to send him two chambered barrels. Sadly, John Olin passed away shortly thereafter and it is unlikely Winchester worked with either. Palmisano also met with Bill Ruger Sr. in the summer of 1975 and pitched their creation. Ruger was interested and assured Lou they’d offer PPC rifles if and when the round became commercially available. In other words, SAAMI blessed along with factory ammunition. The PPC Corporation even committed to underwrite the start-up cost for anyone willing to load the cartridge. However, that wasn’t enough to get the project off the ground. No ammo producer stepped to the plate in the 1970’s and that had to be disconcerting. One representative from a large munitions firm claimed the thirty-degree shoulder would be problematic. He estimated a scrap rate of 20% would result from drawing the profile. It seemed like a poor excuse, but that’s how the story goes. Then in 1978, Remington unveiled the 6mm BR on their 40XB. It seems the short and fat design was taking root, yet again the PPC was passed over. Unexpectedly, Remington did not produce the brass or loaded ammunition. To feed the new 40XB, one had to form it from their small primer pocket .308. Varminters took to the 6BR more than the competitive set. Benchresters stayed with the PPC on Sako brass, shrinking aggs and breaking records along the way. By 1981, the PPC had consumed short-range BR. Of the 60 shooters who made-up the top 20 in the three classes, all but one shot a PPC. And between the two calibers, 6mm was the perennial favorite. Further evidence of the PPC’s success is seen by examining the 179 benchrest records broken between 1975 and 1985. 149 of those were laid with a PPC. If you narrow the time span to 1981 – 1985, all 116 were in PPC chambered rifles. In the cartridge’s first ten years, over one million Sako .220 Russians were imported and sold through the PPC Corporation. Notwithstanding demand, final formed brass and loaded ammunition were not commercially available. Then in 1985, Dr. Henry Cross III requested 10,000 6mm PPC cases. Cross worked with the International Shooters Development Fund (ISDF) and wanted the U.S. Team to evaluate the cartridge. Member were immediately impressed with its performance. They decided to shoot it in the 300-meter Championships of the Americas in 1986 and appointed Lou Palmisano Technical Consultant. Later he was promoted to the Board of Directors of the ISDF. The competition was held at Fort Benning, Georgia in October 1986. Bob Aylward won the 300-meter Free Rifle meet with a 6 PPC. Lones Wigger won the standing 300-meter match shooting the same. The small bore PPC, with an 80 grain flat base bullet, beat the larger, time proven .308 and .30-06. On the heels of that event, Sako flew Palmisano and Pindell to Helsinki. It was time to formally productize the cartridge. The “6mm PPC USA” was born and received a CIP/SAAMI specification. Sako’s 6 PPC differs ever so slightly from the wildcat. The shoulder is five minutes sharper and it headspaces off the outer edge (yes, that’s minutes not degrees). The base is also one to two thousandths bigger so they won’t fit match chambers. Because of these small but significant differences, Lou Palmisano asked Sako to add “USA”. In doing so they demarcated the round from competition spec PPC. Sako chambered the USA for a number of years in their Varminter. In 1993, Ruger followed with .22 PPC and 6 PPC No. 1-Vs. The two made it into their Mk II Model 77 in 1994. The Palmisano & Pindell Cartridge finally achieved a degree of mainstream after years of effort and a sizeable investment. Dr. Lou Palmisano eloquently summarized the journey in 1987 by saying: “It took two guys with a dream to design it. It took the finest, brightest young man I ever knew to test it. It took 4,000 benchresters to prove it. It took two champion U.S. Free Rifle shooter to bring it international fame. And I am grateful to them all” -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Feb 8, 2022 19:49:13 GMT -5

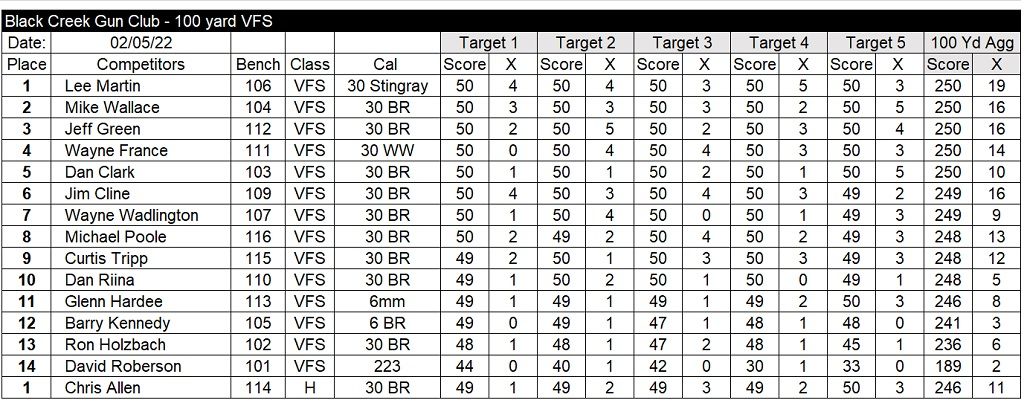

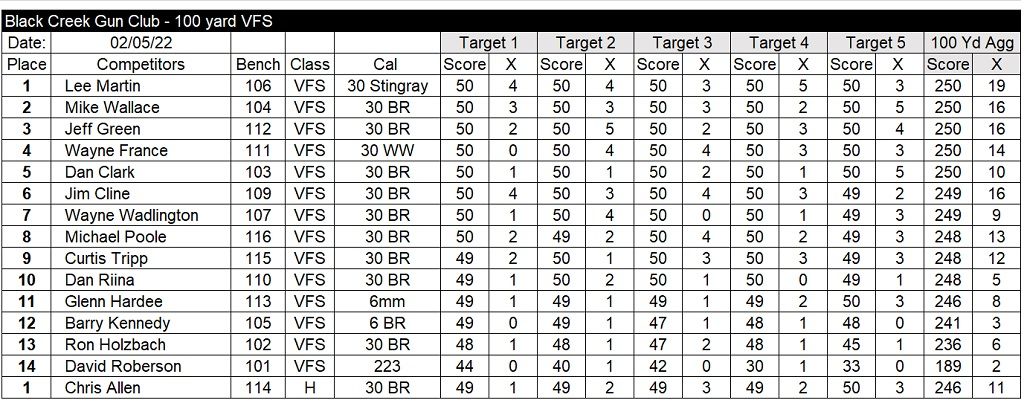

Match #134 Black Creek Gun Club, Mechanicsville, VA IBS VFS 100 Yards __________________________________________________________ This was the first IBS score match of the year. Being our Winter League, the weather lived up to the name. It was 22 degrees when we arrived and by the time the match started, the wind intensified. A persistent 10 – 15 mph push, with gusts well over 20 mph. It was really tricky to get through. You had to be patient. Try forcing shots and you’d drop points. I also found myself shivering while at the bench. Big coats don’t mix well with free recoiling rifles. You also can’t manipulate a 1.5 oz trigger wearing gloves. My gun printed tight throughout and cut the wind better than expected. Shooting on the let-ups, I never held outside the 10 ring and scored a decent X count. That says a lot about how well the load was tuned to the barrel. No bullet is immune to wind, but a stable one gives you a bit of an edge. I predicted before the match started that 20 X’s would be an accomplishment in those conditions. Turns out I was right. 19 X’s took the win.   -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" |

|

cmillard

.375 Atomic

MOLON LABE

MOLON LABE

Posts: 1,996

|

Post by cmillard on Feb 8, 2022 20:30:59 GMT -5

Helluva job well done Lee!

|

|

|

|

Post by bradshaw on Feb 11, 2022 17:44:22 GMT -5

Match #134 Black Creek Gun Club, Mechanicsville, VA IBS VFS 100 Yards __________________________________________________________ This was the first IBS score match of the year. Being our Winter League, the weather lived up to the name. It was 22 degrees when we arrived and by the time the match started, the wind intensified. A persistent 10 – 15 mph push, with gusts well over 20 mph..... You also can’t manipulate a 1.5 oz trigger wearing gloves. My gun printed tight throughout and cut the wind better than expected. Shooting on the let-ups, I never held outside the 10 ring and scored a decent X count.... 19 X’s took the win.  -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" ***** Spoke with Lee the night before this match. I’m well north of Lee, where my casual marksmanship seesaws both sides of the ZERO marking, none of it reaching as high as 32F. Yet, I call the weather for Lee’s first 2022 bench rest match nasty. Not only did he hold consistency through a steady 10-15 mph wind, gusting 20 mph, Lee put down the match-winning 19x25 X-count. A look at the Wailing Wall shows an absence of quitters----a shooter who looses composure after a pulled shot, or series of chased shots, or a shooter intimidated by conditions. The technique of sharpshooting builds on what I call the COORDINATIONS----a rhythmic blend of balance, breathing, sighting, and squeeze. If one of those is off, so is the shot. We talk about the TIMING of a revolver. What about TIMING of the SHOT? The mind is a muscleA bench rest shooter shoots the flags. A silhouette shooter shoots the sight picture. A hunter shoots anticipation. No matter how fast, how slow, each shot is a performance. David Bradshaw |

|

|

|

Post by Lee Martin on Feb 16, 2022 18:37:26 GMT -5

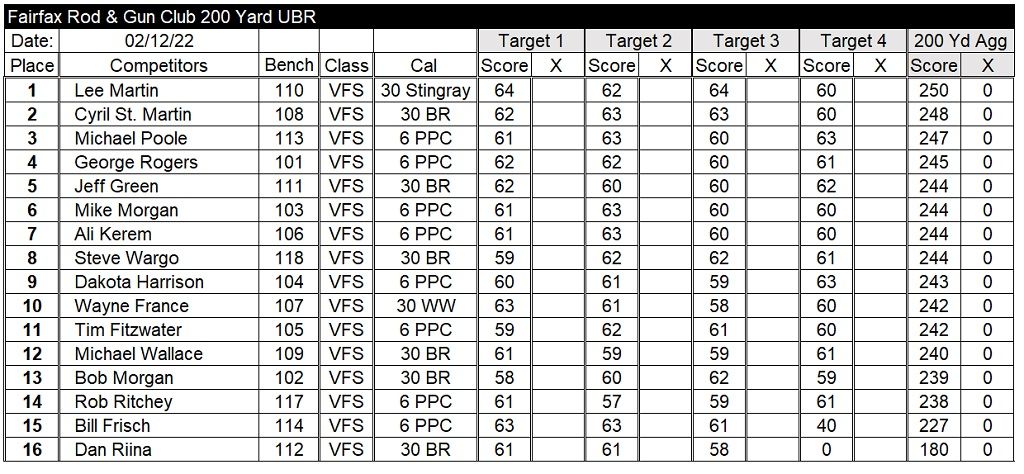

Match #135 Fairfax Rod & Gun Club – Manassas, Virginia UBR VFS 200 Yards _____________________________________________________ We had a mild day to shoot Winter League 200 yard UBR. Unlike the prior Saturday, temps were in the 40’s and we had manageable 5 – 7 mph wind. I’ve talked about the UBR format before, but to recap – the targets are scaled to match the caliber. So, the .30-caliber rings and dot are 0.067” smaller than the 6mm target (0.308” – 0.243”). This levels the playing field. There’s no caliber advantage. Moreover, X’s aren’t scored separately. Instead, they constitute a “11”. A UBR target also has 6 bulls and we shoot four frames. A perfect target, meaning every X is hit, scores a 66. Hitting all 24 across all four targets is a 266 score. My gun was very consistent in the conditions at hand. There was some switch, but most of the day was right-to-left. I found a nice hold at 4:00. Depending on the wind intensity, I either held on the 10-ring line or in-between the 9 and 10 ring. There’s nothing better than a tight shooting gun and your eyes really picking up the conditions. I felt confident with every pull. There’s on old saying in benchrest - if the gun shows it wants to work, trust it. Don’t overthink your shots. Allow the equipment to put you into a rhythm and let the shots go on good looking flag reads. That paid dividends as I didn’t drop any points and nailed 10 X’s. That was good for a 250 final score and the win.  -Lee www.singleactions.com"Chasing perfection five shots at a time" |

|

|

|

Post by potatojudge on Feb 16, 2022 19:00:14 GMT -5

Great shooting, as always.

|

|

cmillard

.375 Atomic

MOLON LABE

MOLON LABE

Posts: 1,996

|

Post by cmillard on Feb 16, 2022 19:41:48 GMT -5

Fine job once again Lee

|

|