Post by Lee Martin on Mar 31, 2015 20:37:55 GMT -5

As William Ruger initiated development of the .357 Maximum, the intent was to provide the impact to topple a 55 pound steel ram from 200 meters, while inflicting less recoil recoil than the benchmark .44 Magnum. A lengthened .357 case fired in a straight chamber would permit interchangeability with .38 Spl. and .357 Magnum. The Maximum would be a hot rod cartridge, devouring a near .44 mag dose of powder in a .357 cylinderr. Ruger partnered with Remington for ammunition. Ruger, Sr., freely expressed consternation as Remington seemed to drag its feet on proving ammunition necessary to testing prototype revolvers. Handloads supplied by this writer could not take the place of commercially-develped ammunition for eventual SAAMI certification. Nevertheless, handloads developed with 180 and 200 grain .358 rifle bullets and fired in prototype SRM revolvers were the main instigator in Remington and Federal producing 180 grain JHPs for the Maximum.

Many shooters, David among them, greeted Ruger's New Model lockwork with reluctance, if not disdain. Out with the melodious clicking safety and half-cock notches. In with a completely passive safety which permits loading without touching hammer and trigger. Upon opening, the New Model loading gate blocks the transfer bar from rising to cover the firing pin. Gate cannot be opened with hammer cocked. Unless the trigger is held to the rear, transfer bar cannot communicate hammer fall to firing pin.

The New Model single action stands beside S&W and Ruger double actions at the pinnacle of fully loaded, safe firearms.

David did not come aboard the New Model train until Ruger released the 10-1/2" barrel S410N Super Blackhawk. The S410N "Silhouette Super" ended the duel between S&W and Ruger. Discovery: the New Model submits to a clean-breaking trigger with strong engagement, with larger engagement patch than Peacemaker-style lockwork. Emphatically, the .357 Maximum would not be the same revolver without New Model lockwork

The revolver progressed faster than the ammunition. Experiment started on a Blackhawk frame, quickly progressed to seven long frame prototypes----stamped SRM-1 through SRM-7----poured at the Newport NH foundry, then machined in Southport CT. (This was 1981. Single action production did not commence at Newport until 1992. All Maximums are Southport revolvers.)

Bill Ruger, Sr., and Jr., were ready to further stretch the SRM frame, as Bill, Jr., considered a case length of 1.660". David worried over frame strength as the bottom strap tapers toward the front. Concerns not shared by Bill, senior and junior. This, while experimental ammo tops 75,000 CUP, primers blanking into firing pin hole, extraction eased by removing cylinder to drive out brass with hammer and drift.

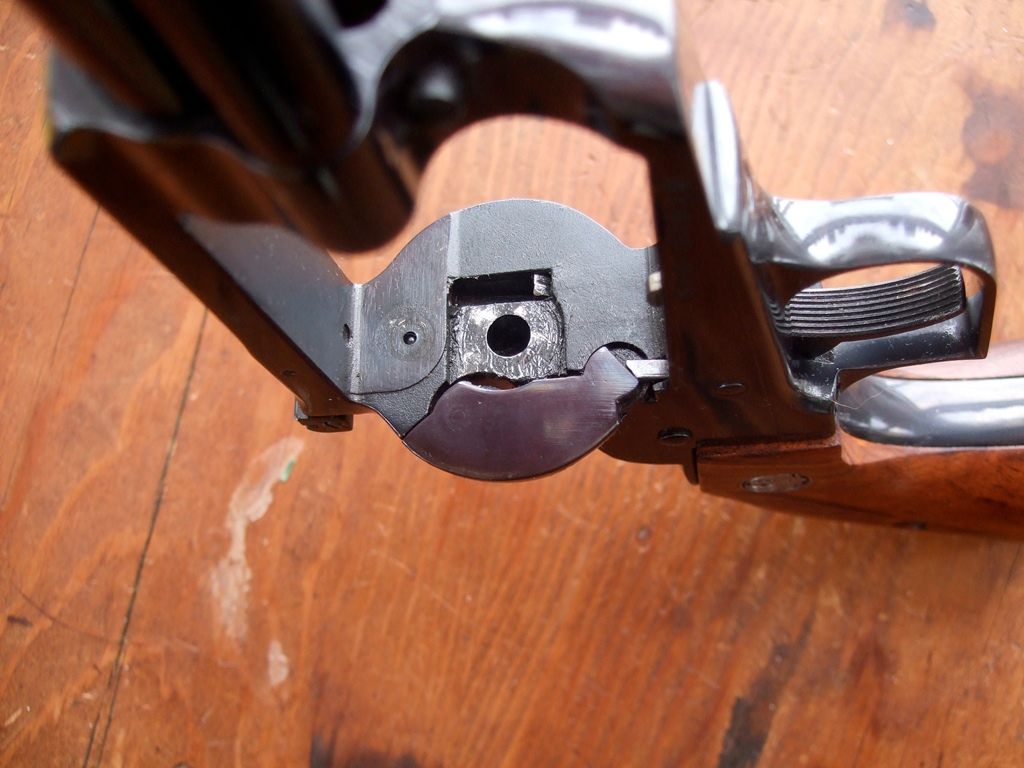

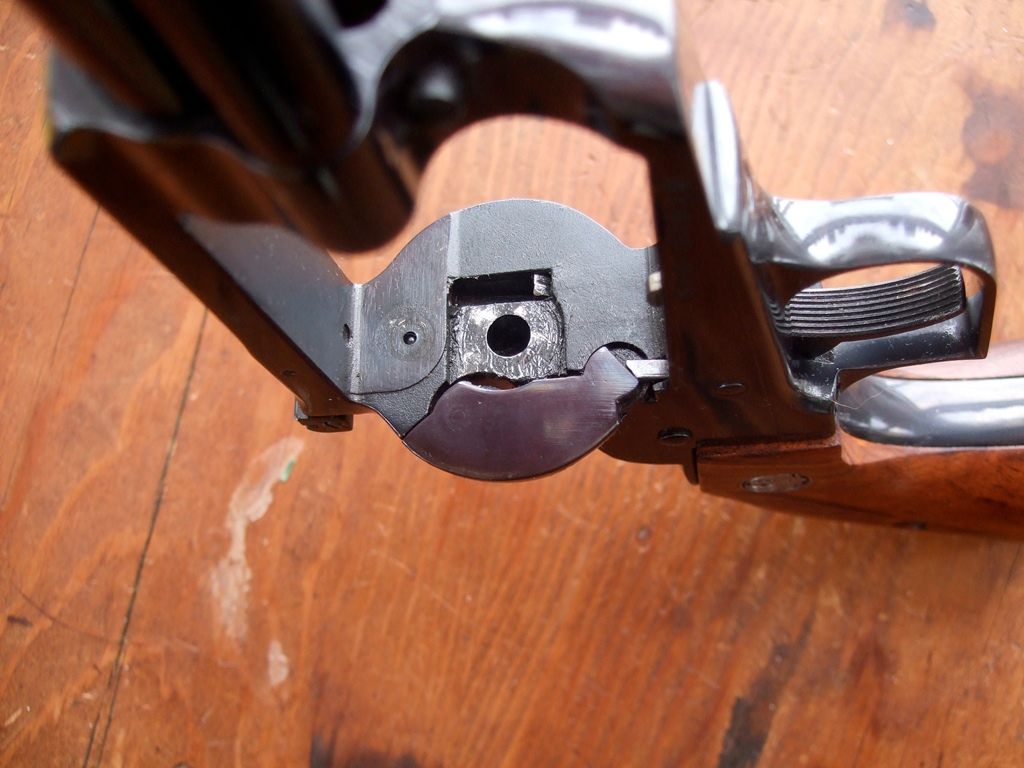

Bill, Jr., settled on 1.605-inch, with the production frame shown here. Remington technicians used closed breech pressure barrels at the Arkansas ammunition plant, and assumed we shot revolvers from a box with a lanyard. Put it this way, Bill, Jr.'s, offer to send an SRM to Remington for in-house ammo testing garnered a less-than Pavlovian response.

Maximum cylinder (right) beside Blackhawk .45 ACP cyl (left) and .45 Colt cyl.

Loads shown, l-to-r:

* 45 ACP----Rem Golden Saber 230 JHP over 8.5/AA #5.

* 45 Colt----cast 276 Volcano, deep seated over 13.5/HS-6.

* 357 Remington Maximum----code 357MX3 180 "Semi-Jacketed Hollow Point.

Frame heat treatment is standard Ruger----strong all the way through. Note standing breech "leade" or ramp into recoil plate area which defines headspace. Loading gate of New model performs three functions

1) access load/unload.

2) drop cylinder catch for rotation.

3) lock transfer bar to prevent cocking.

Cylinder pins for BH/SBH and Blackhawk Maximum.

Bull barrel, indicated by muzzle of 10-1/2", dampens recoil, holds long ejector parallel to chamber.

10-1/2" barrels were fitted with screw-on target blade front sights. Much shooting was done with .100" wide blade. Blades .100" (tenth inch) and .125" (eighth inch) were made. Tenth-inch sight may predominate in production. The 7-1/2" maximum has standard silver-soldered .125" serrated ramp.

.125" target blade shown on 600-00018.

Rear sight notch of .125" is generous for use with .125" front sight on 10-1/2" barrel. Rear notch insert .100" wide (comes with .100" front") is too narrow to properly light sides of .125" blade. Rear notch of .110" to .115" would better match .125" front. (Ruger made a .109" notch in the 1960's.)

Some early Maximums came through with the old 8-click per rev elevation screw. Replaced by 16-click screw around 1982 and production of Maximum. Twice the clicks should provide half the adjustment per; doesn't always work out that way. The 8-click screw tends to better uniformity click-to-click. May not matter for hambone sight-in/leave-it. Matters beaucoup for adjustment in changing light and silhouette

This Maximum sports 8-click screw.

High pressure experimental ammo led Bill Ruger, Jr., to insure chambers were bored straight for smooth extraction. Also, smooth leade (transitions chamber wall to chamber exit, or throat). A .358" throat preferred. Nobody does everything right, and a prevalence of chamber offset among Ruger revolvers is common. A few thousandths barely matters and accuracy camn be saved with a good forcing cone. Chamber misalignment much over .006" and a serious marksman/markswoman will start to notice. Note fouling ring from .357 mag: easily removed.

Ruger incorporated long ejector at David's request to completely extract Maximum case. The Maximum ejector assembly is 1-inch longer than standard and was fitted to first SRM prototypes. Force required to extract brass from brutish experimental loads led Ruger, Jr., to harden ejector rod, carried through on production revolvers. The long ejector was at first tried with the standard spring, which under recoil turned the ejector into a slide hammer against the cylinder face. Effect harder ion ejector than cylinder face. Ejector housing of anodized aluminum, as usual.

Note index finger on ejector button, Maximum case fully extracted.

Barrel-cylinder immediately became an issue with extreme pressure loads. Obviously, to achieve velocity, a large volume of slow powder burning to high pressure wants to be contained. Three dimensions crucial to containment: 1) cylinder gap, 2) throat diameter, and 3) forcing cone; all want to be on the firm side.

Ruger, Jr., tightened gap over standard production without straining assembly. A tight gap requires zero endshake, with cylinder face square to cylinder pin. A film of oil disguises gap in photo, which refuses .0015" feeler. We'll look at gap immediately after firing in Vol. LXV.

Two forcing cones were tried in the .357 Maximum, the industry standard 11-degree, and a 5-degree cone. Bill, Jr., favored 5-degrees, while David sought to continue the 11-degree cone. Nothing wrong with a 5-degree cone----until the base is widened to compensate for chamber-to-bore misalignment. Cut to a given diameter, the low-angle cone sinks deeper into the bore. The bullet now wanders unsupported in search of rifling. Poor bullet, drunk on hot gas, slams wall of forcing cone, ricochets into rifling. The rifling has a drunk slug on its hands, which it works in vain to sober in time for depart from the muzzle. Bullet started life round as a note from Charlie Parker's horn.

Forcing cone pictured is cut short, at 11-degrees.

Identifying rollmark, left side of frame. Super Blackhawk trigger guard. Bill Ruger in mind to introduce the Maximum with his redesign of Colt's Bisley grip. Ruger hoped for interchangeability between SBH and Bisley grips, with an uninterrupted arc at the top. Didn't quite work out that way. The .357 Maximum was released without a Bisley grip, and before Remingon furnished ammunition with 180 grain bullets. David worked with Federal's Hugh Reed to produce a 180 JHP load, as Bill Ruger, Jr., bent Remington's arm for a 180 JHP. Meanwhile, silhouetters stuffed brass with jacketed rifle projectiles and meaty-bone cast.

-Lee

www.singleactions.com

"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time"

Many shooters, David among them, greeted Ruger's New Model lockwork with reluctance, if not disdain. Out with the melodious clicking safety and half-cock notches. In with a completely passive safety which permits loading without touching hammer and trigger. Upon opening, the New Model loading gate blocks the transfer bar from rising to cover the firing pin. Gate cannot be opened with hammer cocked. Unless the trigger is held to the rear, transfer bar cannot communicate hammer fall to firing pin.

The New Model single action stands beside S&W and Ruger double actions at the pinnacle of fully loaded, safe firearms.

David did not come aboard the New Model train until Ruger released the 10-1/2" barrel S410N Super Blackhawk. The S410N "Silhouette Super" ended the duel between S&W and Ruger. Discovery: the New Model submits to a clean-breaking trigger with strong engagement, with larger engagement patch than Peacemaker-style lockwork. Emphatically, the .357 Maximum would not be the same revolver without New Model lockwork

The revolver progressed faster than the ammunition. Experiment started on a Blackhawk frame, quickly progressed to seven long frame prototypes----stamped SRM-1 through SRM-7----poured at the Newport NH foundry, then machined in Southport CT. (This was 1981. Single action production did not commence at Newport until 1992. All Maximums are Southport revolvers.)

Bill Ruger, Sr., and Jr., were ready to further stretch the SRM frame, as Bill, Jr., considered a case length of 1.660". David worried over frame strength as the bottom strap tapers toward the front. Concerns not shared by Bill, senior and junior. This, while experimental ammo tops 75,000 CUP, primers blanking into firing pin hole, extraction eased by removing cylinder to drive out brass with hammer and drift.

Bill, Jr., settled on 1.605-inch, with the production frame shown here. Remington technicians used closed breech pressure barrels at the Arkansas ammunition plant, and assumed we shot revolvers from a box with a lanyard. Put it this way, Bill, Jr.'s, offer to send an SRM to Remington for in-house ammo testing garnered a less-than Pavlovian response.

Maximum cylinder (right) beside Blackhawk .45 ACP cyl (left) and .45 Colt cyl.

Loads shown, l-to-r:

* 45 ACP----Rem Golden Saber 230 JHP over 8.5/AA #5.

* 45 Colt----cast 276 Volcano, deep seated over 13.5/HS-6.

* 357 Remington Maximum----code 357MX3 180 "Semi-Jacketed Hollow Point.

Frame heat treatment is standard Ruger----strong all the way through. Note standing breech "leade" or ramp into recoil plate area which defines headspace. Loading gate of New model performs three functions

1) access load/unload.

2) drop cylinder catch for rotation.

3) lock transfer bar to prevent cocking.

Cylinder pins for BH/SBH and Blackhawk Maximum.

Bull barrel, indicated by muzzle of 10-1/2", dampens recoil, holds long ejector parallel to chamber.

10-1/2" barrels were fitted with screw-on target blade front sights. Much shooting was done with .100" wide blade. Blades .100" (tenth inch) and .125" (eighth inch) were made. Tenth-inch sight may predominate in production. The 7-1/2" maximum has standard silver-soldered .125" serrated ramp.

.125" target blade shown on 600-00018.

Rear sight notch of .125" is generous for use with .125" front sight on 10-1/2" barrel. Rear notch insert .100" wide (comes with .100" front") is too narrow to properly light sides of .125" blade. Rear notch of .110" to .115" would better match .125" front. (Ruger made a .109" notch in the 1960's.)

Some early Maximums came through with the old 8-click per rev elevation screw. Replaced by 16-click screw around 1982 and production of Maximum. Twice the clicks should provide half the adjustment per; doesn't always work out that way. The 8-click screw tends to better uniformity click-to-click. May not matter for hambone sight-in/leave-it. Matters beaucoup for adjustment in changing light and silhouette

This Maximum sports 8-click screw.

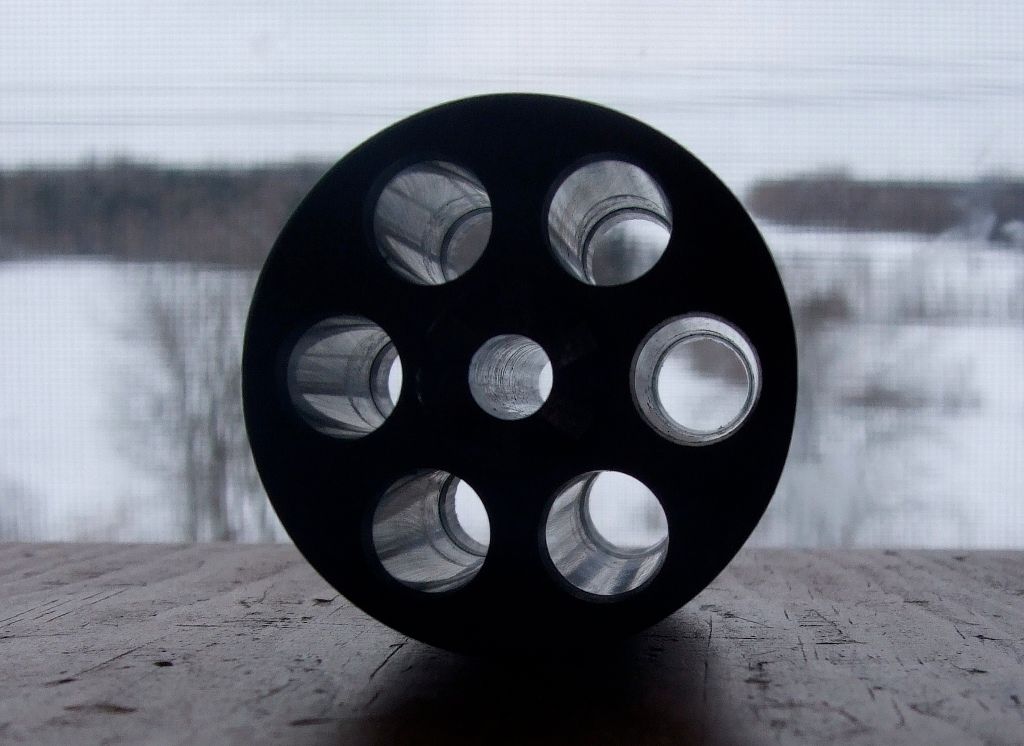

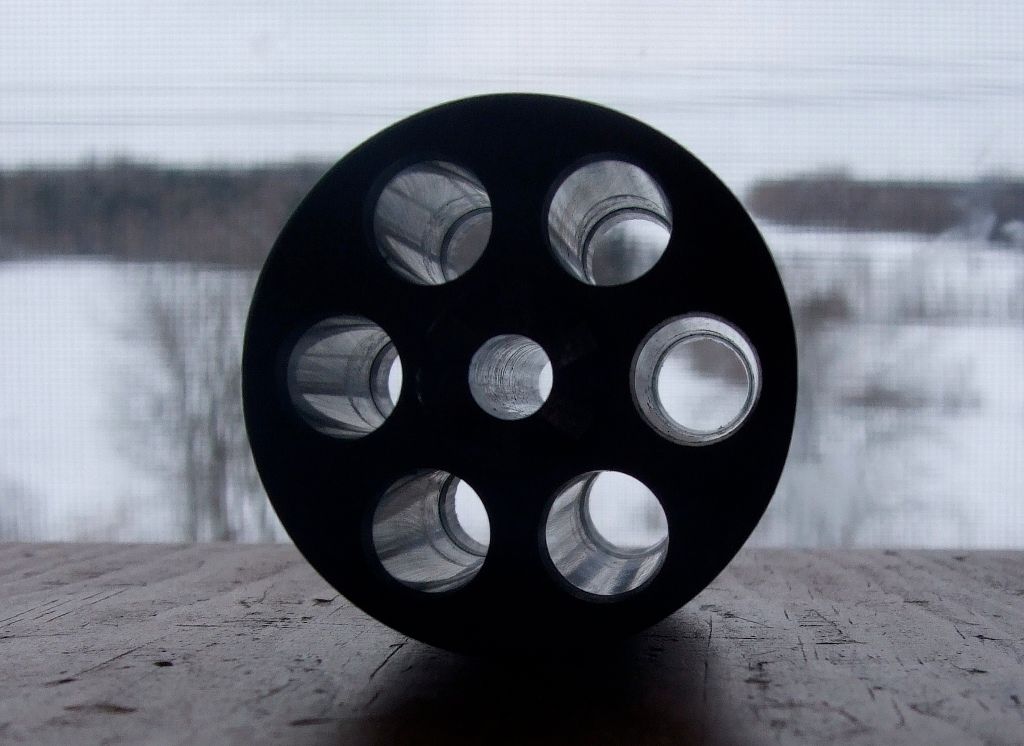

High pressure experimental ammo led Bill Ruger, Jr., to insure chambers were bored straight for smooth extraction. Also, smooth leade (transitions chamber wall to chamber exit, or throat). A .358" throat preferred. Nobody does everything right, and a prevalence of chamber offset among Ruger revolvers is common. A few thousandths barely matters and accuracy camn be saved with a good forcing cone. Chamber misalignment much over .006" and a serious marksman/markswoman will start to notice. Note fouling ring from .357 mag: easily removed.

Ruger incorporated long ejector at David's request to completely extract Maximum case. The Maximum ejector assembly is 1-inch longer than standard and was fitted to first SRM prototypes. Force required to extract brass from brutish experimental loads led Ruger, Jr., to harden ejector rod, carried through on production revolvers. The long ejector was at first tried with the standard spring, which under recoil turned the ejector into a slide hammer against the cylinder face. Effect harder ion ejector than cylinder face. Ejector housing of anodized aluminum, as usual.

Note index finger on ejector button, Maximum case fully extracted.

Barrel-cylinder immediately became an issue with extreme pressure loads. Obviously, to achieve velocity, a large volume of slow powder burning to high pressure wants to be contained. Three dimensions crucial to containment: 1) cylinder gap, 2) throat diameter, and 3) forcing cone; all want to be on the firm side.

Ruger, Jr., tightened gap over standard production without straining assembly. A tight gap requires zero endshake, with cylinder face square to cylinder pin. A film of oil disguises gap in photo, which refuses .0015" feeler. We'll look at gap immediately after firing in Vol. LXV.

Two forcing cones were tried in the .357 Maximum, the industry standard 11-degree, and a 5-degree cone. Bill, Jr., favored 5-degrees, while David sought to continue the 11-degree cone. Nothing wrong with a 5-degree cone----until the base is widened to compensate for chamber-to-bore misalignment. Cut to a given diameter, the low-angle cone sinks deeper into the bore. The bullet now wanders unsupported in search of rifling. Poor bullet, drunk on hot gas, slams wall of forcing cone, ricochets into rifling. The rifling has a drunk slug on its hands, which it works in vain to sober in time for depart from the muzzle. Bullet started life round as a note from Charlie Parker's horn.

Forcing cone pictured is cut short, at 11-degrees.

Identifying rollmark, left side of frame. Super Blackhawk trigger guard. Bill Ruger in mind to introduce the Maximum with his redesign of Colt's Bisley grip. Ruger hoped for interchangeability between SBH and Bisley grips, with an uninterrupted arc at the top. Didn't quite work out that way. The .357 Maximum was released without a Bisley grip, and before Remingon furnished ammunition with 180 grain bullets. David worked with Federal's Hugh Reed to produce a 180 JHP load, as Bill Ruger, Jr., bent Remington's arm for a 180 JHP. Meanwhile, silhouetters stuffed brass with jacketed rifle projectiles and meaty-bone cast.

-Lee

www.singleactions.com

"Building carpal tunnel one round at a time"